Dear Mr. President:

I am writing to you with three different roles. First, I am the director of secondary education and secondary/special education teacher preparation at Seton Hall University where I have been on the faculty since 2002. Second, I am a lifelong educator whose teaching experience at levels from seventh grade to graduate school courses stretches back to 1993. Finally and most importantly, sir, I am the father of two school aged children enrolled in the public schools of New York City. All three of those roles in life have prompted me to write to you, and it is my hope that you will seriously consider what I have to say, for it is based upon my devotion to my children, my experience as a teacher and upon the data that is readily available about what is being done to schools during your administration.

With respect, Mr. President, you are listening to all the wrong people about our nation’s schools.

When you were inaugurated, many of us in education had hoped that your administration would urge Congress to roll back the detrimental aspects of the No Child Left Behind act, which had taken the previous two decades of educational failure rhetoric and placed a punishing regimen of unreasonable expectations, high stakes testing and punishment into effect that left schools and schools systems under threat of a “failure” label if they did not achieve near miraculous score gains in standardized examinations. Instead, we got the Race to the Top program which has taken the worst elements of NCLB and made them even worse. Your signature education initiative incentivized participating states to enroll in rushed and unproven common standards, increases the amount of high stakes testing at all levels of public education, subjects teachers to invalid measures of job performance and creates preferential treatment for charter schools that cynically manipulate data on their enrollment and achievements, sue to prevent public oversight of the public moneys they receive and whose expansion provides new investment vehicles for the very wealthy. All of these results have rich and powerful advocates, and all of them are damaging to our nation’s public schools.

The Common Core State Standards have been described as a state led effort because of the role of the National Governors Association in their creation, but the work of a very few people is far more directly responsible for them. David Coleman, now President of the College Board, Jason Zimba and Susan Pimentel of Student Achievement Incorporated worked with a small group of core writers that were largely representative of the testing and publishing industries to produce K-12 standards in English Language Arts and Mathematics in less than two years. This is a staggering pace for such a complex project, and it was conducted in clear violation of highly regarded and accepted processes for the creation of standards. Dr. Sandra Stotsky of the University of Arkansas was a member of the validation committee that was convened, in theory, to validate the quality of the standards, but she refused to signed off on them when, by her own account, repeated efforts to have the research basis for the standards produced by the writing committees went unanswered. Once written, the standards were rapidly adopted by states due to the incentives of Race to the Top and aggressive spending of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Diane Ravitch of New York University has repeatedly pointed out that this process was staggeringly flawed, and even more flawed than the opaque writing and promotion efforts has been the race to roll out the standards in nearly all states simultaneously with no small scale field testing and no known way for data from the implementation to be fed back to any body that is tasked with revising the standards based on such data.

Mr. Bill Gates seems enormously confident, absent any defensible evidence, that this is the correct path. He provided funding to Student Achievement Incorporated and the National Governors Association, and has been spending lavishly since 2010 to make certain all forms of organizations continue to boost the standards. Mr. Gates spoke this year at the Teaching and Learning Conference hosted by the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (an organization he has given grants to recently), and his defense of national standards was telling. According to the Washington Post:

Standardization is especially important to allow for innovation in the classroom, said Gates, who used an analogy of electrical outlets.

“If you have 50 different plug types, appliances wouldn’t be available and would be very expensive,” he said. But once an electric outlet becomes standardized, many companies can design appliances and competition ensues, creating variety and better prices for consumers, he said.

The version posted to the Gates Foundation website offers a more explanatory framing of the metaphor, but Mr. President, I hope the flaw in his thinking is evident. Multi-state standards are not, inherently, a bad thing, primarily if used like the National Assessment of Educational Progress as a NO STAKES diagnostic tool, and Mr. Gates is correct that a variety of INDUSTRY standards have led to consumer innovations. However, even after we accept a standard for early literacy acquisition to be age appropriate and based on research into how children learn to read, the process by which any given child meets that standard is vastly more complex than the process of attaching an electric motor to a hand blender; worse, it does not demonstrate an understanding that children develop at very varied rates, and that an age appropriate target for one child may be entirely inappropriate for a peer in the same classroom.

Even assuming that Mr. Gates is correct and that CCSS would allow teachers to innovate, Race to the Top and Mr. Gates’ own advocacy have worked to tie the CCSS to a regimen of high stakes testing the likes of which we have never seen and which are already incentivizing teachers and school districts to vastly narrow their teaching in response. Mr. President, policy analysts refer to perverse incentives as those elements of policy that incentivize behavior in such a way that people can obtain the incentive while engaging in practices that are damaging or undesirable. In this case, Race to the Top is the Mother of All Perverse Incentives. Your administration required states to adopt test-based evaluation of teachers in addition to adoption of common standards. This has resulted in states both enrolling in the CCSS testing consortia, and adopting Value Added Models (VAM) of teacher effectiveness as part of teacher assessment and retention. Mr. President, you recently remarked that schools should not be teaching to the test even while your administration was stripping Washington State of its NCLB waiver over its desire to not use high stakes testing to evaluate teachers, but you could do little that incentivizes teaching to the test more than this. Michelle Rhee’s tenure as D.C. Schools Chancellor provides an instructive anecdote. Despite her denials and cursory investigation, it is very clear that her “raise test scores or be fired” approach spawned widespread cheating. That behavior is not excusable, but it is evidence of how far some people placed in extraordinarily difficult circumstances will go when subject to such incentives, and it is simply inevitable that short of cheating, the use of VAMs in teacher evaluation will result in more teaching to the test.

And VAMs themselves are invalid, Mr. President. The American Statistical Association is quite clear on this in its recent statement on the use of VAMs for teacher evaluation.

The measure of student achievement is typically a score on a standardized test, and VAMs are only as good as the data fed into them. Ideally, tests should fully measure student achievement with respect to the curriculum objectives and content standards adopted by the state, in both breadth and depth. In practice, no test meets this stringent standard, and it needs to be recognized that, at best, most VAMs predict only performance on the test and not necessarily long-range learning outcomes. Other student outcomes are predicted only to the extent that they are correlated with test scores. A teacher’s efforts to encourage students’ creativity or help colleagues improve their instruction, for example, are not explicitly recognized in VAMs…

It is unknown how full implementation of an accountability system incorporating test-based indicators, such as those derived from VAMs, will affect the actions and dispositions of teachers, principals and other educators. Perceptions of transparency, fairness and credibility will be crucial in determining the degree of success of the system as a whole in achieving its goals of improving the quality of teaching. Given the unpredictability of such complex interacting forces, it is difficult to anticipate how the education system as a whole will be affected and how the educator labor market will respond.

This is clear-cut, sir. There are no current high stakes tests that meet the requirements of a well developed VAM, and there is no evidence about how VAMs will influence the schools in which they are deployed, but your signature education program is incentivizing them anyway.

To date, no study reliably shows that current VAMs can be used the way they are going to be used over the next few years, but that has not stopped the Gates Foundation from being front and center in this issue as well. The Gates commissioned “Measures of Effective Teaching” study concluded that VAMs can be effectively used to evaluate teachers, but Jesse Rothstein of the University of California at Berkeley demonstrated clearly how flawed the study was, especially how it drew conclusions only weakly supported by its own data:

The results presented in the report do not support the conclusions drawn from them. This is especially troubling because the Gates Foundation has widely circulated a stand-alone policy brief (with the same title as the research report) that omits the full analysis, so even careful readers will be unaware of the weak evidentiary basis for its conclusions…

Hence, while the report’s conclusion that teachers who perform well on one measure “tend to” do well on the other is technically correct, the tendency is shockingly weak. As discussed below (and in contrast to many media summaries of the MET study), this important result casts substantial doubt on the utility of student test score gains as a measure of teacher effectiveness. Moreover, the focus on the stable components – which cannot be observed directly but whose properties are inferred by researchers based on comparisons between classes taught be the same teacher – inflates the correlations among measures. Around 45% of teacher who appear based on the actually-observed scores to be at the 80th percentile on one measure are in fact below average on the other. Although this problem would decrease if information from multiple years (or multiple courses in the same year) were averaged, in realistic settings misclassification rates would remain much higher than the already high rates inferred for the stable components.

It is almost inconceivable how it is that our nation is rushing forward with a package of reforms that are being implemented at breakneck speed with such damaging potential and with so little evidence to suggest that they will do anyone any good, and with mounting evidence that they are objectively harmful. But one thing is actually very certain: these “reforms” and their attendant policies are making some people a substantial profit.

Three years ago, education writer and consultant and former National Board Certified Teacher Nancy Flanagan noted that the rush for CCSS implementation meant that a publishing bonanza was on the horizon. Certainly, their implementation with the coming testing requirements has been a bonanza for Pearson who landed the contract to write and implement the Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) testing consortium. At a predicted cost of 24 dollars for a set of tests as the math and ELA testing comes on line, Pearson is guaranteed a huge new income stream from the more than 10 million students currently in PARCC states. But Pearson is only the most public face of making money off of the reforms put in place by your administration. Common standards and mass testing generate vast amount of data, and technology companies are starting up all intending to mine that data for profit. This is ground that has been ploughed by Rupert Murdoch who, when he began acquiring education technology firms, identified a “500 billion dollar sector” waiting for “big breakthroughs”. Bill Gates has also been involved in this sector, setting up the data cloud storage firm InBloom for 100 million dollars, and watching it close when parental concerns over data security and the plan to allow vendors to access the data could not be overcome. But other firms such as Knewton intend to continue data mining and creating products based upon that analysis, and none of them, regardless of how intriguing their products might be, demonstrate sufficient care about the need to explain their services to parents, the need to allow parents and guardians to opt their children out of the data pool or the need to build real support among the people whose children are being transformed into revenue.

I am asking you as a father, sir: would this be acceptable to you? I regret to inform you, Mr. President, that your own administration has abetted this by changing the regulations that implement the Federal Education Rights and Privacy Act.

Publishers, testing companies and technology firms are not the only ones who are reaping new windfalls from your education policies, Mr. President. It turns out that Wall Street investors are eager to see another aspect of Race to the Top, charter school expansion, continue as rapidly as everything else, and while many of them proclaim to be fans of the charter schools’ alleged “successes” it is also clear that many of them have also figured out how to make guaranteed money from supporting charter schools. Hedge fund billionaires can use a combination of federal tax credits to make investing in charter school construction a vehicle that can guarantee a doubled return within 7 years. This is entirely unlike traditional school construction funding via bond issues because such bond issues are done in the open and for a public with a vote for or against the responsible school boards. This is done entirely in private and with no oversight and precious little public knowledge. It is little wonder then that Wall Street interests are not only investing in charter school construction, they are also organizing PACs such as Democrats for Education Reform specifically to keep state governments granting more and more charters, something else that you enabled with the provisions of Race to the Top.

You might be able to justify this, Mr. President if you could claim that charter schools are actually the solution to American education, but to make that claim you would have to ignore evidence. Many charters are excellent schools. Many are terrible. But there is no evidence that the charter school segment is consistently outperforming fully public schools. There is, however, evidence that charter schools do not educate children with disabilities at comparable levels as fully public schools. There is evidence that charter schools do not serve students who are English Language Learners like their fully public peer schools do. There is evidence that one of the most prominent charter operators in New York City, Eva Moskowitz of Success Academy, is not telling the truth about the number of children in poverty that she serves, the real achievements of her schools test scores, or the rate of attrition for students with disabilities and language learning issues.

These schools are not miracle factories, Mr. President, but supporting their expansion is making people money. Your Secretary of Education, Arne Duncan, once opined that Hurricane Katrina was the “best thing” ever for New Orleans Schools because it shook up the status quo and got people “serious” about reform. That “reform” has meant that this week, the last public school in New Orleans has closed for good, and the city school system in entirely comprised of charter schools. Amidst growing evidence that many prominent charter operators are not equally educating students and amidst disturbing studies about rising segregation in the charter sector, I cannot help but wonder how Secretary Duncan justifies his statement today.

No wonder teacher morale is at an all time low.

Your public voice in these issues has been a disaster for you, Mr. President. Secretary Duncan may be the most controversial person to hold that office since its creation, and he has repeatedly demonstrated that he is both insensitive to teacher and parental concerns and fully vested in a false narrative about American education. Mr. Duncan has frequently repeated to charges from corporate reformers and privatizers that American education is stagnant and that we can infer a need for their favored reforms from international testing data. This is part of a narrative of deepening failure which thoroughly ignores how American students have never fared well on such measures and how these scores and our economic health have little connection. Mr. Duncan has observed that he believes our teachers are not educated enough and we should be more like South Korea, despite the fact that South Korea’s educational “success” comes with high costs: 20% of family income on average spent on private “cram” classes, focus on drill and rote learning that leads to high test scores, and wide recognition that South Korean children face too much pressure, leading to an alarming youth suicide rate. This is hardly praise worthy, sir.

Secretary Duncan’s misunderstanding extends to why people are criticizing the CCSS and other Race to the Top reforms. I am sure that you know how he said that Common Core opponents are often “white suburban moms” who are upset to find out their children are not “as brilliant as they thought they were”. Mr. Duncan apologized for the remark, but his insinuation that any opposition to CCSS is unreasonable betrays that he really does not understand the issue. Mr. President, American parents, by wide margins, believe that the schools their children attend are doing very good work, and despite three decades of an unrelenting failure narrative, that percentage, over 70%, has remained stable. What parents are saying is that Common Core, evaluating teachers by tests and the increase in high stakes testing and heavy pressure on schools to raise test scores at all costs have come too rapidly, with too little transparency, and with extreme negatives vis-a-vis how children experience school. Mr. Duncan does not understand that as evidenced by his remarks in April with NY Commissioner John King where he called parental protests “drama and noise.” Mr. Duncan may call the 10s of 1000s of families who have opted out of Pearson’s testing and the list of districts refusing to field test the exams “drama and noise”. Many, myself included, call it a movement that is ignored and dismissed at peril. I do not know if your Secretary of Education has told you that most opposition to reform comes from Glenn Beck styled cranks and spoiled suburbanites, but if he has, you have been sorely misinformed.

Mr. President, in 1999 Congress passed the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, also known as the Financial Services Modernization Act, and President Clinton signed it into law. Although the trends in mortgage lending and investment products that led to the financial crisis had begun long before 1999, the removal of regulations that prevented commercial and investment banks and insurance firms from blending their businesses greatly accelerated the damage being done to our financial industry.

Mr. President, I am afraid that history will look upon Race to the Top as your Financial Services Modernization Act, a tool crafted to be cynically misappropriated by interests with no concern for the public good.

And what is so frustrating, Mr. President, is how entirely unnecessary this judgment of history will be. Our schools need help, sir, but it is not help that will be found by racing to implement new standards, layering on more high stakes tests, threatening teachers’ livelihoods with invalid statistical models or by turning more and more of our urban school districts over to for profit charter school corporations. Our schools are afflicted by the same thing that afflicts our society: rising poverty and constant cuts to assistance for the poor. 16 million children in the United States live in poverty; that is 22% of all children, 38.2% of all African American children and 35% of Hispanic children. Our schools serve communities, and our segregation by income has increased over the past 30 years, meaning that both rich and poor increasingly live in communities with people mostly of their own income level. The Residential Income Segregation Index (RISI) scores for Houston, Dallas, New York, Los Angeles and Philadelphia are all above 50, and the RISI has gone up in every region of the country since 1980. Nationally, it is 46, an increase of 39% since 1980.

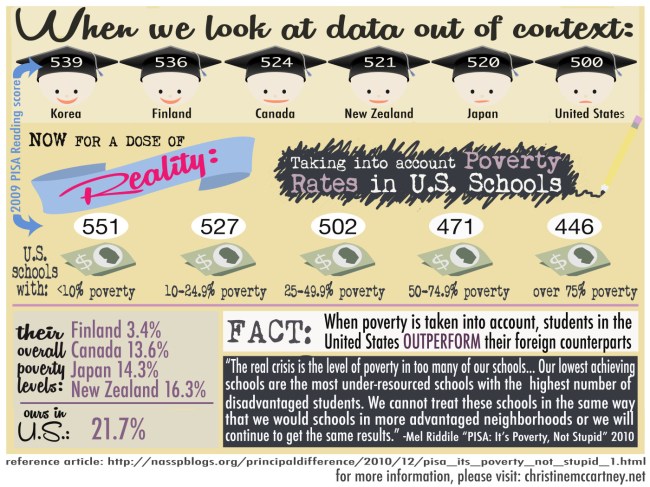

We see this when we look at our PISA scores broken down by the income characteristics of communities. According to USC Professor Emeritus Stephen Krashen, the portrait of America’s schools look very different when poverty characteristics are considered. In schools where less than 10% of the students qualify for free and reduced lunch, our PISA scores are higher than the average for any OECD nation, but where 75% or more of students are in poverty, the PISA scores are second to last. Given that our communities are increasingly segregated by income, Mr. President, it is inevitable that test score data compared nation to nation will be misleading.

It is at this point that Arne Duncan, Michelle Rhee, Joel Klein, Eva Moskowitz, Andrew Cuomo, Bill Gates, Whitney Tilson, and a host of other corporate “reformers” will line up to accuse me of making “excuses” for “bad schools”. They will insist, absent any evidence, that “great teachers” can close the achievement gap even if we completely fail to address poverty in our communities. But it is not “making excuses” to insist that if we want a child living in poverty to succeed in school that we cannot ignore whether or not she knows if she is going to eat tonight, or if she will have a place to sleep, or if her parents will continue to work or any of the host of other matters that afflict children in poverty in ways that negatively impact their formal education. Mr. President, we have known the long term impacts of poverty on children for some time now just as we have known that it has been growing and deepening, and we spend far less than our peer nations on helping to alleviate the detrimental impacts of poverty. Nothing in education policy in the past three decades has done anything to address that.

That is not “excuse making,” Mr. President, that is aiming the analysis at the actual problem, whether or not addressing the problem will make anyone a profit.

You have an advantage that few of your predecessors had, Mr. President, and it is your demonstrated interest in and ability to genuinely listen to others. Joshua Dubois wrote about your meetings with the families at Sandy Hook Elementary School, and how for hours, you sat, embraced, asked questions and listened to them. What strikes me, sir, is how, despite an election year warming up, you never once mentioned this to the press and never once used this remarkable testament to your character for political gain. I urge you, Mr. President, to visit teachers, parents and children in the same manner, without cameras or vetting, and just ask them what they want our schools to be. You will not find their answers easily mapped onto your education policies.

It is not too late for you to have a transformational impact on America’s schools, Mr. President, but it will take a number of immediate actions to have a chance. I ask you to consider the following, badly needed, steps:

- Scrap Race to the Top: Your signature education policy is detrimental to children, teachers, schools and communities. Ending it will not do away with the Common Core State Standards, testing or charter schools, but it will free states and districts to look truly reflectively at these initiatives and to voluntarily engage in as little or as much of them as they deem necessary and beneficial. It will require proponents of these policies to make their cases in full view of the public in all 50 states instead of hiding behind coercive requirements for federal funding.

- Restore Federal Privacy Protections: Technology entrepreneurs may have truly powerful learning tools in development, but to make them work, they need student records deemed private under federal law. Instead of engaging teachers and parents about these tools, they got your administration to revise regulations and are now mining those records without any meaningful consent. This is unacceptable, and it must stop. Our children are not sent to public school to be monetized without our consent. Parents will listen to open and honest efforts to describe how these tools can benefit their children, but they will oppose efforts to bypass them.

- Be Serious About Holding Charter Schools Accountable to Civil Rights Legislation: Your administration recently expressed interest in making certain that charter schools meet federal civil rights requirements. This is a good first step. It must be applied vigorously, especially given how poorly many high profile charter operators do in serving students with disabilities, educating English Language Learners and retaining students of color after admission. Your administration has granted enormous favoritism to charter schools, and they must be made fully accountable.

- Demand a Marshall Plan for School Aid and Construction: Nearly all states are spending less money per pupil today than in 2008. In New York State, the average school district still receives $3.1 million less in state aid than they would have without budgetary tricks like the Gap Elimination Adjustment. All across the country, our public schools are being told to implement a complex new curriculum, meet unrealistic testing requirements and to do so while having their budgets cut to the bone. Further, in 2008, the AFT commissioned a study that estimated a need for over $250 billion in school infrastructure spending nationwide, a need that remains unmet. It adds insult to injury that students come from homes that suffer from the deprivations of poverty and arrive in schools that are cold in the winter, hot in the summer and wet when it rains. Our nation must do something about this. At the same time, you must highlight schools where children in poverty thrive, not merely where they get good test scores.

- Replace Secretary Duncan: Mr. Duncan is entwined so deeply in the Race to the Top approach to reform that he is incapable of moving away from it. Your Secretary of Education demonstrates no understanding of why people oppose current reforms, little willingness to see his mistakes as more than verbal slip ups, and he consistently misuses international test data to denigrate the quality of our schools and teachers. If you want to protect our schools from the forces of corporate reform, Secretary Duncan cannot lead.

You have an opportunity, Mr. President, to retask the federal Department of Education with protecting our national Commons, our history of 200 years of seeing public education as a public good for communities and a private good for individuals. Your administration has abetted the use of our public schools by private and corporate interests in ways that are actually detrimental to education. If you wish that to not be your legacy, you must act now.

Sincerely,

Daniel S. Katz, Ph.D.

Director, Secondary and Secondary/Special Education Teacher Preparation, Seton Hall University

Career Educator

Father of Two Public School Children