New Jersey’s public schools welcomed a new governor last month, after a bruising 8 years of Chris Christie. It is not necessary to recap all of the previous administration’s battles with the state teachers union and his numerous insults to individual teachers (although Rutgers graduate student and career educator Mark Weber has a handy summary here). Governor Murphy promises to be a much more progressive figure in New Jersey politics, and he has pledged to move the state away from some legitimately damaging Christie-era policies. During the campaign, Governor Murphy promised to withdraw New Jersey from the PARCC assessments and to implement shorter tests that give teachers and students actual feedback, to fully fund the state’s education aid formula, and to walk back from state takeovers and other top down policies. Early indications suggest that he is in earnest about these promises and that New Jersey is moving in a different educational direction.

This is a good start, but New Jersey’s school problems are deeper than funding, inappropriate tests, and the overall demeanor of its governor. This is not unique to New Jersey. States across the country reeled from the effects of the Great Recession, and a wave of disruptive policy initiatives impacted schools systems in every state of the Union. Governor Murphy faces a New Jersey where state aid remains underfunded, where the impacts on classrooms of standards reform and the PARCC examinations are still significant, and where recruitment of new teachers has suffered along with teacher morale. While funding and curriculum/testing reform are significant endeavors that need the new governor’s attention, he must also look towards an impending problem for all of New Jersey’s school: the teaching profession is far less attractive today than it was a decade ago, and without a strong plan to reverse that, funding and curriculum changes will falter.

A recent bill advocated by New Jersey Senator Cory Booker would help, somewhat. Financial incentives to become a teacher and to stay in the profession are welcome and overdue, but it is only a portion of the problem. Economic incentives alone will not make teaching as a profession more attractive because the roots of our current problems are not tied solely to economics. This is also not a new phenomenon. The prevalence of “psychic rewards” in teaching was noted by Dan Lortie in his landmark study “Schoolteacher” and their nature are both subjective and highly individualistic, largely because of the highly uncertain aspects of teaching itself. In short, very few seek to become teachers because of the fame and money, and since the most prized rewards of teaching are vulnerable to the “ebb and flow” of classrooms and schools, it is easy to see how teacher morale can plummet. Pull too hard on what makes the work worth doing and fewer people will want to do it.

So what has happened in New Jersey that has impacted our ability to recruit and retain teachers?

First, New Jersey has restricted who can even consider becoming a teacher. Through multiple changes to the state code, New Jersey has raised the GPA entrance and exit requirements for potential teachers, raised the entrance exam requirements for teacher education so that only the top third of test takers can become education majors without passing additional examinations, has added the Pearson administered edTPA performance assessment on top of the PRAXIS II examination as an exit requirement, and has expanded student teaching into a full year experience. All of these initiatives have one obvious impact: many fewer graduates of New Jersey’s high schools can even consider teaching as a profession. This may have a certain intuitive logic and hearkens back the Reagan administration’s “A Nation at Risk” which lamented how many of America’s teachers were among the poorest students in college. Two problems are associated with this perspective, however. While there is certainly evidence that teacher knowledge matters, there is scant evidence that the knowledge reflected in high standardized test scores is closely correlated with becoming a good teacher. Indeed, struggling in an endeavor can lend a great deal of insight for a potential teacher, and in two decades in higher education, I have seen many students who clearly had requisite knowledge and who brought valuable experience to teaching struggle on a standardized test that said very little about them. Second, the very students that New Jersey has declared are the only ones eligible to seek teaching as a profession are also students with a great many options in front of them. Even if they are not drawn to teaching for wealth, they surely want their classrooms to be places that are satisfying to them as professionals.

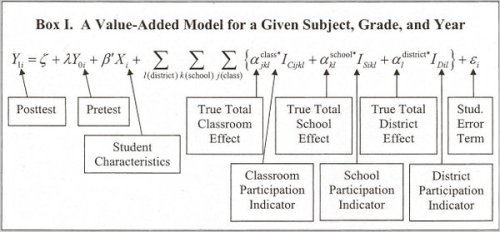

So what do New Jersey teachers currently find in their classrooms? For teachers in tests subjects, up to a third of their evaluation rests on Student Growth Percentiles (SGPs), a form of valued added calculation that attempts to compare teachers’ impact on tested subjects with their students. While SGPs are simpler than other growth measures, that does not mean they are less controversial, and studies in New Jersey highlight how closely correlated SGPs are to demographic and resource characteristics as opposed to individual teacher inputs. While Governor Murphy promises to withdraw New Jersey from the PARCC assessments, any replacement assessment would still be figured into the current teacher evaluation system.

All teachers, including ones in tested subjects, also complete the Student Growth Objective (SGO) annually. When I first heard about the concept — teachers selecting an annual project for improving their teacher and working closely with administrators — it certainly seemed full of potential. Reality, unfortunately, has been rather different. The SGO manual describes a process that is cumbersome and limited to “growth” projects that produce measurable results which effectively means using tests of some sort of another. The busy work aspect of SGOs as practiced is clear on page 19 of the current manual:

A keen observer might wonder upon what basis “adding or subtracting 10%” is remotely a valid method of determining what range of student performance indicates different levels of competency, and that same observer would be right to suspect that these instructions are far more about producing tables that are quick and easy to read in an office in Trenton than they are about helping teachers and supervisors genuinely reflect upon and improve practice. A process like this, tied to evaluation, invites the worst of bureaucratic responses that go through the motions without really engaging in genuinely student or teacher learning. I would challenge Governor Murphy to visit teachers and try to find out how many simply give students a test on material that hasn’t been taught early in the school year so that the final SGO evaluation can demonstrate “growth.” Don’t blame teachers, though – blame a process that lends itself to compliance without substance.

The current situation is one that Governor Murphy has inherited, and it goes far beyond disruptive standardized tests and the disposition of the occupant of Drumthwacket. New Jersey currently sits with a tightly constricted teacher pipeline on one end of teacher preparation, and a profession that is saddled with an evaluation system based upon measures ranging from statistically dubious to bureaucratically mind numbing. Imagine the irony of recruiting high caliber students into demanding preparation and sending them into an evaluation system that fails to treat them as professionals and you can grasp the difficulty of convincing young people to pursue teaching.

Fortunately, there are fixes to the current problems in New Jersey, some relatively easy and others more complex. Governor Murphy should consider adding flexibility to who can enroll as education majors in the state. If keeping the pool of potential teachers academically talented is important, it should, nevertheless, be possible for students who are not among the strongest test takers to demonstrate their competency through GPA targets in non-introductory semesters, an allowance that would give students incentives to stay on track and allow for students making a difficult transition to college expectations to find their academic footing. The Governor can also reconsider the state’s commitment to the edTPA performance assessment which is both expensive and needlessly complicated. For several years I have told my students that edTPA is “not the worst thing in world,” but since the worst things in the world also include smallpox and diphtheria, that is not an exceptionally high bar to pass. The basic components of edTPA are already well known in teacher education – assess student needs, design instruction to meet those needs, teach, and then assess the impact of that teaching — in the form of Teacher Work Sample and other performance assessments. The difference with edTPA is that it is externally evaluated by the Pearson Corporation and it uses a language for analyzing teaching that matches nothing teacher education or professional development has ever widely used before, creating barriers for communication with cooperating teachers and school administrators. Finally, since it is scored securely by a third party, the edTPA is a massive project for prospective teachers during their student teaching that nobody who knows their work and their teaching context can provide significant, formative feedback.

New Jersey should convene a meeting with the leaders of Schools of Education and set parameters for locally derived performance assessments based upon the earned expertise of the education researchers, the experienced classroom teachers, and the supervising administrators involved in student teaching experiences in New Jersey. We are more than capable of doing so, and many of us were doing so for many years before the state told us we cannot be trusted with the task.

The Garden State can also take steps to trust teacher expertise and professionalism in the classroom by moving strongly away from the SGP and SGO components of assessment that both drive up the importance of standardized testing and take enormous amounts of time in an exercise with little value. Partisans for the education reform environment from 2010 forward will argue that the standardized test based assessment system is indispensable because it dispenses with the “lies” about what students are actually learning. Considering how narrowly standardized tests actually define learning, this argument betrays an awful lack of imagination. It is not necessary to abandon standards and rigor while simultaneously engaging teachers and administrators in real processes that use locally produced assessments and support the growth of structures that actually support teacher growth. Linda Darling-Hammond of Stanford University provides a detailed outline for such systems in this 2012 report, a substantial jumping off point for policy makers who are interested in evaluation premised on growth and support, an entirely new direction in New Jersey at this point.

If Governor Murphy fulfills his promises on education, he will have a decent start. However, the problems facing New Jersey schools run deeper and right into the systems that have been set up over the past decade. The Garden State is narrowing the pool of available teachers in ways that are unnecessary, and it is subjecting those teachers to professional assessments that are both unfair and wasteful once they enter the classroom. A new set of professional structures, developed in full partnership with community education stakeholders and premised on support and growth, would be a far greater incentive for young people to commit to a career in the classroom and to keep them there once they have begun teaching. More flexibility for young people entering and exiting teacher preparation would not negatively impact teacher quality while keeping the door open for more promising candidates who are drawn to this profession because of their personal desires to do good in the world. It will take a while to figure this out, but it will be worth it.