Like many states from the former American frontier, Kansas has a long, and often proud, history of offering free public education for its citizens. The territory’s first free public school in Council Grove was established in 1851 for the children of white government workers and others who traveled along the Sante Fe trail. In 1858, the Territorial Legislature authorized the office of Territorial Superintendent of Common Schools and County Superintendents, beginning the process of opening common schools within walking distance of most eligible students. The 1861 Constitution of the new state of Kansas recognized the need for a uniform system of Common Schools and schools for higher grades as well.

By the 1870s, so-called “log schools” were established across Kansas, and in 1874 the first compulsory school attendance law was passed requiring students between the ages of 8-14 years old attend a 3-4 month school year. The state wanted to promote more than a primary education by 1885, and public county high schools were developed. Like many states, the earliest teacher credentials merely required a demonstration of basic literacy, but Kansas followed national trends in the late 1800s to implement more stringent requirements for acquiring a teaching certificate, and the state board began accrediting teacher education programs in 1893.

Kansas was at the center of the fight to overturn school segregation when the Topeka Board of Education fought to maintain its segregated school system all the way to the Supreme Court in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. Although the Topeka Board of Education was on the wrong side of the case, that loss paved the way for active integration efforts that continued throughout the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s until efforts stalled after Ronald Reagan’s election. In many respects, the story of public education in Kansas reflects the story of public education across many of our nation’s states: progress, both voluntary and compelled, slowly ensuring that the scope and promise of public education reaches more and more citizens.

Kansas may just be done with all of that nonsense.

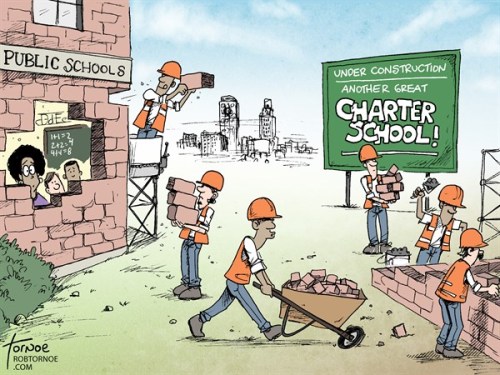

Governor Samuel Brownback’s pledge to turn Kansas into a laboratory of conservative, small government experimentation is certainly well known by now – as is the havoc that it has unleashed upon tax revenue and economic growth. Governor Brownback’s budgets have slashed deeply into Kansas primary, secondary, and higher education on multiple occasions, and his 2015 budget hacked another $44.5 million, and cuts amounting to another $57 million are on the table for this year. Spending on public schools has been so inadequate that in 2014, the Kansas Supreme Court ordered the legislature to increase spending and to use that money to alleviate funding disparities between districts. While the highest court asked a lower court to reconsider its order that spending increase statewide by an eye watering $400 million a year, legislators were essentially ordered to get adequate funding to poorer districts. Lawmakers and the Governor failed so spectacularly at that task that the Kansas Supreme Court ordered them in February of this year to fix the matter by June 30th.

One might think that after years of self-imposed budget shortfalls standing between Kansas legislators and their Constitutional obligation to fund schools, that someone in Topeka might take a moment to reflect upon the sustainability of their desire to cut government to the bone. Someone, you might expect, might ask that if they cannot find the money to provide the most widely agreed upon functions of government – a functioning common school system – then what are they doing to the future of Kansas?

Kansas legislators would prefer to impeach judges than actually fund their schools. Instead of impeaching judges for misconduct, the proposed law, which had the immediate support of half of the state Senate upon introduction, would allow for impeachment over attempting to “usurp the power” of law makers or the governor. The bill passed the Kansas Senate and now sits in the judiciary committee in the House where it is unlikely to meet much opposition. The message Kansas law makers are sending? Don’t tell us when we are violating our Constitutional obligations to fund an appropriate education for all children in Kansas — shut up and let us keep cutting taxes.

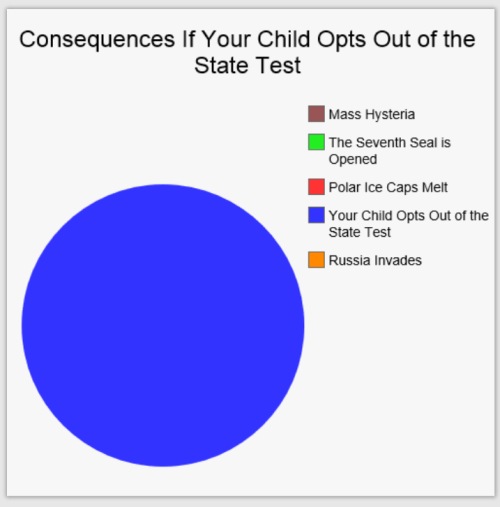

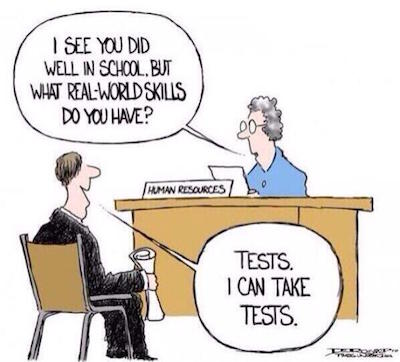

If you think it could not get possibly worse, you lack the destructive imagination of some Kansas lawmakers. Introduced in House Bill 2741, which was filed just before a month long recess, is the Kansas Education Freedom Act – a potential final nail in the coffin of public education in the Sunflower State. Under this plan, parents would be able to take 70% of the funds allocated for per pupil aid in their district and use it to pay for private schools, online schools, homeschooling, or private tutors. While the legislation would require education in certain core subjects, oversight of that would fall to the State Treasurer instead of the Department of Education, and students educated under these funds would not be subject to the state tests used to assess district schools. And just to rub a little more salt in the wounds of public schools, the legislation restricts spending of state funds so severely that it cannot be used for school meal programs and even extracurricular activities such as band that have courses connected to them might not be able to use state money.

70% of per pupil funds – gone. The moment a family selects to pursue an option, basically any option, other than the district school.

Vouchers have been tried in several major cities over the past few decades, and their record – on increasing access to additional options, on improving student outcomes, on improving public schools via competition, and on general school finances – is nothing to brag about. The Kansas legislation proposes opening the door for public school funds to be sent to online charter schools even though recent studies demonstrate that such schools have “an overwhelmingly negative impact.” Even the pro-charter school organization The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools found the results so disturbing that they said they were “a call to action” for policy makers. It also seems odd that a state desperately trying to slash its education costs would propose sending money to students and families who would normally cost the system very little – students attending private schools or being home schooled. If this passes, each one of those students will cost the state 70% of a student attending a local school.

But beyond these alarming cautions is another, even more disturbing, implication of the bill: the complete abandonment of public education as a PUBLIC endeavor premised on equity and pluralism. The scheme worked out in the “Kansas Education Freedom Act” is to essentially tell families that the only purpose of an education is to maximize what they can individually get out a marketplace. In the long history of public education in America, it is very hard to find examples of completely abandoning the public purposes of compulsory education such as civic education and community based ideals such as pluralism and equity. H.B. 2741 basically chucks that in favor of a mad dash to grab resources for individuals instead of making sure that all individuals live near quality resources. It is not difficult to predict how parents with means at their disposals will use this legislation to elbow others out of their way.

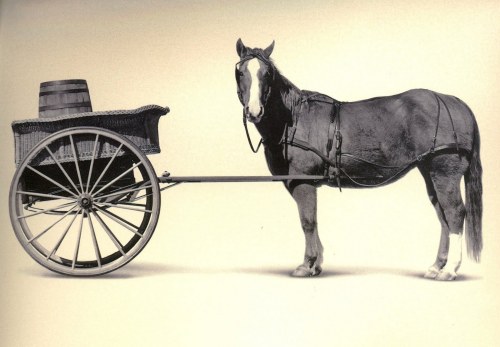

Voucher proponents have always papered over concerns about access and equity in their schemes largely because their favored mechanisms – marketplaces – are designed specifically to provide great variation in quality based on ability to pay. But it is very different to say that it is okay that the car marketplace allows some people to buy Bentleys while others buy used cars; it is entirely another to say that someone should seek out the equivalent of a 1987 Yugo for a child’s education. Since vouchers have not historically opened a wide range of options for poorer families, let alone a wide range of quality options, the likely outcome of H.B. 2741 will be to simply transfer public money to people already seeking private education, decreasing community stakes in local schools and, by extension, local communities.

Kansas wrote its commitment to public education directly into its Constitution in 1861. Is 2016 the year that it says it is done bothering with it altogether?