David Tyack and Larry Cuban, two of America’s most accomplished scholars in education, published the book “Tinkering Toward Utopia: A Century of Public School Reform” (1995) examining various efforts to reform American education and explaining why schools tend to persist regardless of changes envisioned by reformers. The book, arguably one of the best treatises on the subject in the past two decades, opens by noting how it is possible to portray American education as either evidence of progress or of regress depending almost entirely upon the motivations of the examiner:

Beliefs in progress or regress always convey a political message. Opinions about advance or decline in education reflect general confidence in American institutions. Faith in the nation and its institutions was far higher in the aftermath of success in World War II than in the skeptical era of the Vietnam War and Watergate. Expectations about education change, as do media representations of what is happening in schools. And the broader goals that education serves – the visions of possibility that animate the society – also shift in different periods, making it necessary to ask how people have judged progress, from what viewpoints, over what spans of time. (p. 14)

Tyack and Cuban take great care to demonstrate that much of our concept of progress or regress in education depends greatly upon how we frame questions and what questions we ask (or fail to ask). For example, the great wave of educational expansion in the Progressive Era was influenced by the reformers’ beliefs that education could mold society for the better and that their progress was clearly reflected in statistics that showed greater and greater numbers of Americans obtaining more and more education. At the same time, however, these same Progressives built a system with systemic inequalities enshrined in legally enforced segregation in some states and de facto segregation in others, with deep differences in school funding depending upon location, with limited college and career opportunities for women, and with few efforts to meet the educational needs of children with disabilities. The federal government’s Bureau of Indian Affairs set up a system of boarding schools for native children that were expressly racist and traumatizing. The point here should be clear: whether or not schools are progressing is a consideration awash in choices of focus, not merely in data.

Today, Americans are in the third decade of an intense effort to convince them that the nation’s schools are failing. Steeped in the rhetoric of existential threats in the Cold War, the Reagan administration released “A Nation at Risk: The Imperative of Education Reform” in 1983, which declared, in no uncertain terms, the belief that the education was not merely failing, but that it had already, definitively, failed:

If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today, we might well have viewed it as an act of war. As it stands, we have allowed this to happen to ourselves. We have even squandered the gains in student achievement made in the wake of the Sputnik challenge. Moreover, we have dismantled essential support systems which helped make those gains possible. We have, in effect, been committing an act of unthinking, unilateral educational disarmament. (p. 1)

President Reagan’s commission made such dire pronouncements at an opportune moment. Having had confidence in the government shaken by both the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal and having had confidence in our economic future beaten by declines in heavy industry, oil crises, stagflation, and back to back recessions, Americans had already lost confidence in education generally. As Tyack and Cuban (1995) note, in 1973 Gallup polling reported that 61% of Americans thought their children would get a better education than they had gotten, but by 1979 that number had fallen to 41%. But the authors also note that in 1985, while Americans did not have a high opinion of the national school system, only 27% of the them rating it as an A or a B, parents with children in school rated those schools highly, 71% of them giving a grade of A or B to the school attended by their oldest child. That discrepancy has remained notably stable over the decades. In the 2014 version of the same poll, 17% of Americans rated the national school system as earning an A or a B while 67% of parents gave that grade to the school attended by their oldest child.

While that second number has been trending lower recently, it is note worthy even after three decades of constant criticism of our schools that a super-majority of parents remain favorably disposed to the schools they know the best. In the past decade and a half, that criticism has become omnipresent with a bipartisan selection of politicians demanding more and more of our schools and with private foundations and billionaire financiers pushing reforms to increase test based accountability in public education and to use what they see as evidence of failure to demand market-based changes to how we deliver our educational commons. Microsoft founder and philanthropist Bill Gates burst into a public role demanding education reform in 2005 by declaring our entire system of education “obsolete”. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan now famously opined that Hurricane Katrina was “the best thing that happened to the education system in New Orleans” because it provided the impetus to dramatically change the schools in the city, and the result is that the New Orleans school district is the first in the nation to be comprised entirely of charter schools. Secretary Duncan’s words, insulting to the many who lost loved ones, homes, and livelihoods in the hurricane, make it clear that he believes hugely disruptive change is an imperative in education today.

But what if that is, from a variety of perspectives, unnecessary? What if the story of American education is one of steady and cumulative progress and success? What if the needs of our schools and the students in them are better seen from the perspective of systemic support rather than from systemic turmoil and disruption? What if our leaders, both in politics and in business, are choosing to see American education in terms that can only be addressed by unleashing “creative destruction” without regard to the quantifiable goods that will be unpredictably harmed or dismantled by that force?

In 1993, the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Education Research and Improvement, released an omnibus report entitled “120 Years of American Education: A Statistical Portrait“. The report, presented in charts and graphs, demonstrates a steady progression in the reach of education from relatively small enterprise encompassing mostly a white and male population in the mid-1800s to a national enterprise available to and used by the majority of our population. In many respects, it tracks the growth of American enfranchisement because as different populations in the country have been granted access to the right to vote and to protection from discrimination, their engagement with our educational commons has expanded as well. So at the risk of taking a stance that Tyack and Cuban would acknowledge as political, I would like to present some of these findings as reasons to be thankful that previous generations of Americans invested meaningfully in an educational infrastructure as crucial to our economic health as our transportation, power, health, and water systems and as important to the vitality of our culture and psyches as our libraries, national parks, civic cultural institutions.

The growth of access to education and the depth of completion of education in the history of our common schools movement is evident. In 1850, 56.2% of white children aged 5 to 19 years of age were enrolled in some form of schooling while only 1.8% of black children and children of other races were similarly enrolled. By 1910, those numbers had climbed to 61.3% of white children and 44.8% of black children and children of other races, and by 1970, the numbers were 90.8% and 89.4% respectively, climbing to 93.1% and 93.2% in 1991. In 1940, the percentage of males who completed 4 years of high school was 12.2% and 5.5% had 4 years or more of college for a median of 8.6 years of schooling completed, and the percentage of women who completed 4 years of high school was 16.4% and 3.8% had 4 years or more of college for a median of 8.7 years of schooling completed. By 1991, 24.3% of males over the age of 25 had 4 years or more of college for a median of 12.8 years of schooling, and 18.8% of women over the age of 25 had 4 years or more of college for a median of 12.7 years of schooling. Black men and men of other races only had a median of 5.4 years of formal schooling by age 25 in 1940, but that number rose to 12.6 years in 1991 with 17.8% of black men and men of other races having 4 or more years of college. Black women and women of other races had a median of 12.5 years of completed school by 1991, and 15.8% of them had 4 or more years of college.

Over this time frame, illiteracy in the general and specific populations decreased. In 1870, 20% of the population over the age of 14 was considered illiterate as defined by not being able to read or write in any language. That percentage was a staggering 79.9% in the black population, but by 1910 the total illiteracy rate had decreased to 7.7%, and the rate in the black population had dropped to 30.5%. Black illiteracy rates remained above 10% through 1952, but by 1979, they had fallen to 1.6%, and illiteracy in the total population was down to 0.6%.

Our nation’s schools were rarely accommodating places for students with disabilities with little to no recognition of specific learning disabilities until the 1970s. In 1931, only 0.6% of children enrolled in schools were recognized as being disabled and in programs, and those were mostly speech, visual, and auditory disabilities with another large group of children recognized with cognitive impairments. In the mid-1960s, this had grown to 4.3% of public school enrollments, but still without recognition of specific learning disabilities. Due to litigation and legislation, this changed in the 1970s, and by 1989, 11.4% of the student population was served by special education programs with 2,050,000 children receiving accommodations for learning disabilities.

Student achievement as measured by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) has made slow but steady gains in the decades since the federal government began the program. In 1970-71, the average 17 year-old scored 285 in reading, 304 in mathematics (1972-73 data available), and 296 in science. These scores rose slightly by 1990 to 290 in reading and 305 in mathematics, and fell slightly to 290 in science. Black and Hispanic students made more notable gains in the NAEP during this time. In 1970, black 17 year-olds scored 239 in reading, 270 in mathematics (1972-73 data available), and 250 in science (1972-73 data available). By 1989, these scores rose to 267, 289, and 253 respectively. For Hispanic students, reading scores of 252 in 1974 rose to 275 in 1989, math scores of 277 in 1972 rose to 255 in 1989, and science scores of 262 in 1976 remained stable in 1989. Gains in the NAEP for higher level proficiencies also occurred across racial groups. For example, level 300 in mathematics in the NAEP at high school is defined as being able to perform elementary algebra and geometry. In 1977, 57.6% of white students scored in this range as did 16.8% of black students. By 1989, those percentages had risen to 63.2% and 32.8% respectively.

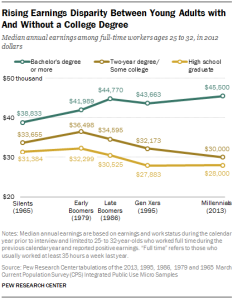

Pursuit of higher education has also grown dramatically in the United States. In 1869, 1.3% of the population aged 18-24 was enrolled in higher education of any form. This number did not rise to 10% until 1945, but in the post World War II period it grew steadily, reaching 23.6% of the population in 1961, 41% of the population in 1981, and 53.7% of the population in 1991 with public institution enrollment of over 10.7 million split between 4 and 2 year schools. In 1910, only 20 persons out of 1000 aged 23 had a bachelor’s degree, and by 1990, that number rose to 282 out of 1000 persons aged 23 years. In 1990, the nation conferred 454,679 associate degrees, 1,049,657 bachelor’s degrees, and 323,844 master’s degrees. It is noteworthy that female degree recipients outnumbered men in all of these categories when they lagged behind men in both bachelor’s degrees and master’s degrees as recently as 1980.

American educational progress did not end in the data for the 1993 report. Educational attainment numbers rose between 1990 and 2013 across the board, with high school diploma acquisition rising to 94% of whites, 90% of blacks, and 76% of Hispanics. The percentage of 25 to 29 year-olds with a bachelor’s degree rose to 34% of the total population, with white degree earners rising from 26% to 40%, black degree earners rising from 13% to 20%, and Hispanic degree earners rising from 8% to 16%, although the gap between groups in degree attainment did rise despite the nominal gains. Women built on their previous gains, widening to a 7% difference in bachelor’s degree attainment from the 1990 data, and by 2013, 9% of women had a completed master’s degree compared to 6% of men.

Achievement results have also grown, although sometimes slowly, in this period. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, 4th grade assessments grew between 1994 and 2010 with very slight gains in the upper percentiles of children taking the assessments, but with more dramatic gains in the lower quartile of test takers. Children in the 25th percentile saw their average scores rise from 180 to 192, and students in the 10th percentile grew from 147 to 169. The 2010 report notes that only a quarter of students tested rated as “proficient”, but that for 4th an 8th graders, the gains in proficiency from the 1994 data year was significant. Further, gains in the NAEP assessments for black and Hispanic test takers in 2010 represented a narrowing of the achievement gap compared to the 1994 data.

It is important to remember that Tyack and Cuban argue that portrayals of education in progress or regress is frequently a political choice, and I have to confess that there are real and legitimate questions to ask of our schools. Although schools have admirably followed the continuous, if slow, expansion of the American franchise with the expansion of educational opportunity, many of our schools, much like the communities in which they reside, languish with dilapidated facilities, outdated resources, inexperienced or overworked teachers, high class sizes, students who struggle, and community constituencies that are overlooked or actively disenfranchised by our political system. And for the 31 years that we have been subjected to constant narratives of failing schools, our society has disinvested in infrastructure, seen its unionized workforce collapse, and largely accepted vastly growing income inequality as a fact of modern economics. These trends only contribute to the deeply entrenched poverty in many of our urban and rural centers, and they highlight the now well known difficulties of getting ahead when one is born into poverty. Worse, another growing trend in America, our rising residential segregation by income, means that those who are economically secure rarely even see the decayed streets, crumbling schools, and closed small businesses that more and more of our citizens live with routinely.

It is little wonder that schools struggle in communities with such problems. Schools are social institutions, and when an entire community’s institutional infrastructure struggles to meet basic needs, it is tragic but hardly surprising when schools similarly struggle. Education “reform” today, unfortunately, looks at those very schools and does not merely demand that they do better; it demands that they essentially take on the responsibility of transforming their entire communities with practically nothing demanded from society as a whole. The great progress that we have made with our educational commons since the late 1800s did not happen by simply demanding more and layering more and more responsibility. It came because we, as a society, invested heavily in the creation of a common school system, and then we took vigorous actions to open up access to more and more members of our society.

If we want to push through this lingering, neglected, frontier of educational opportunity in our country, we will need to become serious about everything that is necessary to rebuild our communities that suffer from inter-generational poverty by pouring in resources, and we will need to seriously demand an economy where full time work is properly rewarded, making education an obtainable means to a genuinely obtainable end. Improved and revitalized school systems in these locales can be an critical part of revitalization — but they cannot bring that about on their own.

Our continued educational progress will not hinge on increased demands so much as it will hinge on increased support.