Abstract

Efforts to reform teacher education in recent years have focused on demands for higher quality candidates and indicators of rigorous preparation without careful consideration of the total policy environment in which such preparation must take place. In the era of test based accountability, efforts to recruit, prepare and induct qualified and passionate new teachers are severely hampered by contradictory and high stakes priorities enacted by state level policy makers. In this article, I locate the different policy pressures that make thoughtful and effective teacher preparation less likely and explain what teacher preparation would look like if we took a systemic and developmental approach to teacher education that recognized how teachers learn. Policy makers need to understand the interconnected nature of their decisions and offer policies aimed at support and growth of teachers at all experience levels and at development of capacity in universities, schools, school districts, and state offices.

###

It is, of course, easy to criticize the reform plans for teacher education that are in various stages of implementation in New Jersey. Most proposed changes exist either as evidence-free assertions that “more is better” or as potentially defensible proposals whose consequences remain unexamined. Perhaps most importantly, they exist in tandem with other policies in both teacher preparation and education in general that seem to contradict their central premises of attracting only the best students to teacher preparation and holding them to rigorous professional standards. Demonstrating those contradictions is an exercise that lends itself to sarcastic wit and to taking potshots at those in authority, a two for one deal that is difficult to resist.

More daunting, however, is putting forth a positive vision of what teacher preparation ought to look like if we accept the premise that all involved would favor seeing passionate and able young teachers take to our classrooms after being strongly prepared to meet the challenges of teaching. One does not have to seek out the poorly supported declarations of agenda-driven, self-appointed “teacher quality” watchdogs to find negative assessments of teacher preparation; they are deeply embedded in the popular culture which frequently asserts that teachers are “born” rather than made. These assertions are expertly addressed here by David Berliner, past president of the American Educational Research Association. However, it is important to note that a belief in teaching as a craft whose knowledge cannot be learned outside of experience is common among teachers themselves and strongly related to teacher education’s continued struggles to provide meaningful contexts for practice prior to teaching (and the reality that no controlled practice environment is fully sufficient to represent full time teaching under any circumstances).

Those of us who labor in good conscience for the preparation of tomorrow’s teachers need to articulate visions of that preparation focused upon the needs of teachers and their students. My goal here is to detail concerns and priorities that should exist at three different stages of teachers’ professional preparation: recruitment, preparation, and induction.

Recruitment

Becoming a teacher is unlike training to join most other professions in no small part due to our apparent familiarity with teaching and teachers. Dan Lortie, in his landmark 1975 work, Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study, observed that a typical student spends 13,000 hours observing teachers teaching during the course of a K-12 education. That is a remarkable level of familiarity that does not exist for professions like law, psychology, medical doctors, or nurses, and, as Lortie notes, it takes place in fairly close quarters and frequently develops interpersonal relationships as well. A strong theme among people seeking to become teachers is a desire for continuity in the experience of school; having enjoyed school themselves and having developed meaningful relationships with teachers during the long “Apprenticeship of Observation,” many teachers enter the profession desiring not to begin anew, but rather to continue. While the apprenticeship is lengthy, it can also be deceptive because, as Lortie notes, the student’s vantage point is substantially different from the teacher’s, and it does not lend itself to viewing teaching via pedagogy and the goal-setting orientation that drives teachers’ decision making. Regardless of the limitations of student perspectives, they do matter for future teachers, many of whom seek a teaching career based upon those perceptions and the personal value derived from them.

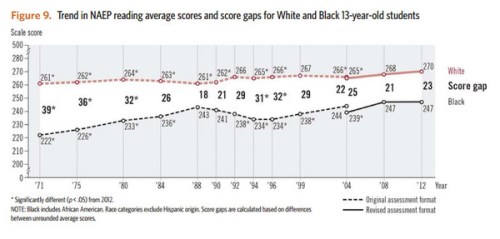

If future teachers develop deep seated beliefs about teachers and teaching during their prolonged experience in school, we should want that experience to convey a powerful vision of meaningful learning upon them. Our current policy environment of “test and punish” which was instituted under the No Child Left Behind act and placed into overdrive with Race to the Top has resulted in a more narrow curriculum focused upon tested subjects and a deep decline in teacher satisfaction with their jobs. Between 2008 and 20012, teachers who are “very satisfied” on the job declined from 62 percent to 39 percent, a 25 year low, and the percentage of teachers who report that they are “under great stress” several days each week rose to 51%. A curtailed curriculum and dissatisfied teachers who cite lack of time for professional development and collaboration with their colleagues are not ingredients for P-12 schools that will nurture the next generation of teachers. In fact, recent evidence from the United States Department of Education shows enrollment in teacher preparation programs, including alternate route programs, dropping 10% overall nationwide with several state, such as California where applicants for teacher preparation shrunk by 53%, showing steep declines.

Policy makers need to pay especially close attention to the working conditions of teachers not merely because those conditions impact teacher satisfaction and student learning, but also because it impacts the building of professional commitment by future teachers. The idea of future teachers building their commitment throughout their long apprenticeship in P-12 education is related to the concept of teaching as vocational work, a concept that has been unwisely disregarded in this era of high stakes accountability via measurement. David Hansen of the University of Illinois at Chicago wrote in 1994 that teachers develop a sense of their work as vocational through dispositions and through their tight connection to the very specific social context of teaching and enacting teaching. Hansen writes that seeing teaching as a vocation…

…suggests that the person regards teaching as more than simply a choice among the array of jobs available in society. It may even mean for such a person that there is something false about describing the desire to teach as a choice at all. An individual who is strongly inclined toward teaching seems to be a person who is not debating whether to teach but rather is contemplating how or under what circumstances to do so. He or she may be considering teaching in schools, in institutions of higher education, or in one of the many other social setting – from military bases to visitors’ centers – in which teaching can occur. But it may be years before such a person takes action. He or she may work for a long time in other lines of endeavor – business, law, parenting, the medical field – before the right conditions materialize. This posture in fact describes may persons who are entering teaching today. To describe the inclination to teach as a budding vocation also calls attention to the person’s sense of agency. It implies that he or she knows something about him or herself, something important, valuable, worth acting upon. One may have been drawn to teaching because of one’s own teachers or as a result of other outside influences. Still, the fact remains that now one has taken an interest oneself. The idea of teaching “occupies” the person’s thoughts and imagination. Again, this suggests that one conceives of teaching as more than a job, as more than a way to earn an income, although this consideration is obviously relevant. Rather, one believes teaching to be potentially meaningful, as a the way to instantiate one’s desire to contribute to and engage with the world. (pp. 266-267)

We would do well to remember this concept for several critical reasons. If we want young people or career switchers to become teachers, we have to accept the variety of reasons why people make the decision to teach. Lortie’s observation that many teachers seek continuity with an experience they themselves found desirable reminds us to enable working conditions that foster teacher satisfaction, student learning, and a positive disposition towards teaching among future teachers. Excessive test preparation, teachers without time to collaborate positively with colleagues, and general stress among teachers and students act as disincentives for otherwise interested students to consider teaching and may distort vocational aspirations.

It also should caution us about the type of person who becomes interested in teaching under such circumstances, as Lortie also noted that the desire to continue in school also contributed to teacher conservatism, the impulse to replicate existing practices. Hansen’s vocational framework deepens this dilemma because for a person to act upon a sense of vocation in a particular field there must be a field where the individual’s desire to serve and to contribute can be enacted. Jobs incentives such as pay and benefits matter, but they will be insufficient if a potential teacher sees a field dominated by distorting policy initiatives that focus work upon aspects that detract from the sense of motivating purpose. When accountability ceases to be a monitoring activity that reflects upon teacher effectiveness and becomes a goal in and of itself as it has in test-based accountability, we risk undermining the critical sense of self which motivates students to become teachers.

In addition to attending to the school climate that shapes potential teachers and the sense of vocation they develop prior to teacher education, policy makers need to consider what they are looking for as requirements for prospective teachers. Many policies are aimed at driving up the academic qualifications of students seeking to become teachers, and a frequently cited “fact” about why this is important is because high performing Finland supposedly only accepts the “top 10%” of students to become teachers. While it is true that only 10% of applicants for spots in teacher training programs are accepted at Finnish universities, it is not exactly true that they are all the “top 10%”. In fact, according to Pasi Sahlberg, a Finnish educator and visiting professor at Harvard University, Finland’s teacher preparation programs seek applicants from across the academic spectrum in attendance at university, and they do this because “…successful education systems are more concerned about finding the right people to become career-long educators” and because the best students are not always the best teachers. It is actually likely that students who have at least some experience struggling in school will be far more receptive to the need to differentiate their teaching and will know from experience that students can need a variety of supports in order to succeed with challenging material. State policy makers and university based teacher preparation should look far beneath simple test scores to identify prospective teachers with genuine commitment and passion for teaching and learning.

Preparation

Situated between 13,000 hours of being a student in teachers’ classrooms and entering a profession of millions of fellow teachers are four, short, years for undergraduate teacher preparation. Consider Lortie’s warnings about teacher sentiments. If the long apprenticeship of observation leads prospective teachers to strong ideas about what teaching is, but those ideas cannot encompass all of the real work that makes teaching happen, and if the desire for continuity with previous school experiences leads teachers to conservatism by favoring smaller scale changes, if any, then a four year undergraduate teacher preparation experience is a necessary step to help prospective teachers enlarge not only their knowledge and teaching repertoire, but also to enlarge their vision of what teaching and learning actually are. It stands in stark contrast to alternative pathways into teaching that rely upon teachers training on the job and without space and time to fully embrace what their work means.

Consider Maxine Greene’s warning in her 1978 essay Teaching: The Question of Personal Reality where she writes about teachers without self knowledge encountering the school system:

The problem is that, confronted with structural and political pressures, many teachers (even effectual ones) cope by becoming merely efficient, by functioning compliantly—like Kafkaesque clerks. There are many who protect themselves by remaining basically uninvolved; there are many who are so bored, so lacking in expectancy, they no longer care. I doubt that many teachers deliberately choose to act as accomplices in a system they themselves understand to be inequitable; but feelings of powerlessness, coupled with indifference, may permit the so-called “hidden curriculum” to be communicated uncritically to students. Alienated teachers, out of touch with their own existential reality, may contribute to the distancing and even to the manipulating that presumably take place in many schools….Looking back, recapturing their stories, teachers can recover their own standpoints on the social world. Reminded of the importance of biographical situation and the ways in which it conditions perspective, they may be able to understand the provisional character of their knowing, of all knowing. They may come to see that, like other living beings, they could only discern profiles, aspects of the world.

Greene’s argument points to a vital role for undergraduate teacher preparation in coaxing future teachers to understand themselves and others not merely for self reflection but also to understand that all knowledge is provisional and to value the perspectives their own students will bring with them, greatly expanding the possibilities of their own teaching. Andy Hargreaves argues that while Lortie and his successors have presented “conservatism” as a professional trait, it is actually best regarded as a “social and political ideology and power relationship,” so change “must first be needed, wanted and acknowledged” if any of the characteristics inhibiting change in teaching are to diminish. Like Greene’s analysis, this is intensely personal and not an endeavor likely to be completed without significant time and space to challenge deeply rooted assumptions about how teachers teach and how students learn, especially students whose lives do not reflect the experiences of our mostly white, mostly middle class, teaching corps.

Gary Fenstermacher expands upon John Goodlad’s concept of teaching as practicing “stewardship” to include “a deep and thorough understanding of the nature and purpose of formal education in a free society.” Learning to teach, then, requires a genuine commitment on the part of programs and participants to explore dispositions that allow prospective teachers to see their work not only as a continuation of their own school experience, but also as a set of experiences with potential transformative power for both their students and society. Teacher education that does not lay that gauntlet at our students’ feet risks thoughtless replication instead of empowering improvement.

Undergraduate preparation is also an important, and sheltered, environment in which future teachers develop professional knowledge and repertoires to use in the classroom. While popular sentiment, as mentioned previously, suggests that teachers only “know” what their students learn, that sentiment is uninformed by what it takes to transform content into something pedagogically powerful that lasts for students. I actually sympathize with teachers who groan when someone comes along with a new “best way” to teach that is typically a repackaging of long-known ideas into a new textbook and professional development workshop series. On the other hand, behind a lot of academic rhetoric are critically important concepts for teachers that can be effective frameworks for practice. Linda Darling-Hammond notes that significant research demonstrates routes to teaching that lack significant pedagogical training and student teaching result in teachers who only have generic teaching skills of limited range.

Darling Hammond, however, cautions university programs against complacency, especially in critical aspects of preparation such as developing deep content and pedagogical knowledge as well as closely tying university and school based preparation together. Many programs have extended preparation time, and a growing number of university based teacher preparation programs have expended the time and resources to develop school based partnerships where prospective teachers gain richer opportunities to practice what they are learning in environments that encourage them to learn from those experiences. It is worth noting that when done well, such partnerships go far beyond developing teachers who can consistently check off the right ticky boxes on the Danielson framework. Darling Hammond notes that the most promising teacher preparation practices “envision the professional teacher as one who learns from teaching rather than one who has finished learning how to teach…” We are, in fact, talking about a stance towards professionalism as beginning with strong skills and continuously learning and developing rather than simply achieving specific point ranges on a rubric.

Sharon Feiman-Nemser characterized the central tasks of teacher preparation as “analyzing beliefs and forming new visions, developing subject matter knowledge for teaching, developing understanding of learners and learning, developing a beginning repertoire, and developing the tools to study teaching.” To accomplish such tasks, teacher preparation programs need “conceptual coherence” meaning programs need to be organized around central principles that inform the structure, content, and assessment of courses and experiences and sequences them so that prospective teachers have the best possible chances to develop their abilities. Articulating a conceptual vision is not simply slapping a “mission statement” on a website, then; rather, it is a core set of beliefs guiding decision making and how evidence is used for program development.

Programs also need “purposeful, integrated field experiences.” This critical component to teacher preparation allows prospective teachers to gain practical experience applying their growing knowledge and teaching repertoire, and it allows them to test teaching theories in supported environments. Feiman-Nemser notes that promising programs include a variety of activities for prospective teachers in the field that prompt them to think critically about their experience so that the traditional divide between theory and practice is lessened. Kenneth Zeichner writes that the traditional disconnect can be diminished by programs creating “hybrid spaces” where the expertise and knowledge held by teachers is given equal footing with the academic knowledge housed at university campuses. He further notes that a growing body of research demonstrates that teacher preparation programs that coordinate course activities and assignments with “carefully mentored” field experiences better prepare teachers who are able to “successfully enact complex teaching practices.”

Undergraduate programs further need to pay “attention to teachers as learners.” Programs have to prompt their students to challenge and extend their existing assumptions about teaching and learning, and they have to actively help them challenge those assumptions “in response to students’ changing knowledge, skills, and beliefs.” As Feiman-Nemser points out, this is not merely a disposition to be fostered in prospective teachers, but also it is one that should be modeled by program faculty who engage in teaching methods they expect of their students. Such preparation to teach and to learn from teaching serves the interests of program graduates’ future students, and it gives the graduates skills they will need to make best use of their need to learn and develop when they enter the profession full time.

It should be noted that elements such as these in teacher preparation require more than program faculty who are conscious of these elements and conscientious about the need to make certain all teacher candidates enjoy preparation guided by these principles. Elements of this work are entirely within the control of teacher education programs, and, notably, state level policies on the qualifications of teacher candidates have very little impact upon them except to narrow the pipeline of potential future teachers. However, other elements depend heavily upon state and local policies, and they can be negatively impacted by them. Zeichner notes that the kind of clinical work that is necessary for teacher education to be effective is still rarely valued at research universities, and that faculty who take the time and effort to foster genuine two-way ties with practicing teachers suffer detrimental consequences to their careers. Further, in a time of continued cuts to state support for higher education, it is exceptionally hard for university programs to build and scale the kinds of meaningful partnerships in local schools needed to prepare prospective teachers. If we expect teacher education to provide excellent preparation, policy makers need to facilitate the necessary elements of that preparation.

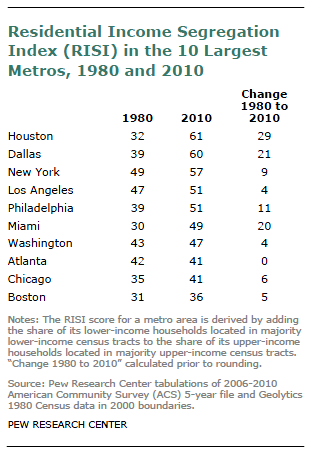

Also, we need policy makers to consider the environment that they are pushing into our public schools. Teaching is a time consuming and demanding profession even under ideal circumstances; increased demands upon teachers with no changes in their other work requirements serves as a disincentive to accept novices in their classrooms. The impacts of state policies on teachers is no small matter. In New Jersey, all teachers have to submit Student Growth Objectives as part of their annual evaluation, and while the early explanation of SGOs suggested a potentially valuable process of self examination with the support of administrators, the reality is a time consuming mess for which teachers have received little training and even less time. Page 16 of the state distributed SGO Guidebook is a textbook case of instructing people to create meaningless tables that resemble statistical analysis but bear absolutely no resemblance to statistics done with any integrity. Teachers in subjects that are tested in the PARCC consortium exams are also evaluated using Student Growth Percentiles (SGPs) which have some advantage over value added models by being relatively stable but which are also statistically correlated with the percentage of children in poverty. Bruce Baker of Rutgers sarcastically and correctly questions the validity of SGPs since they only seem to work if we assume that, somehow, the only truly effective teachers in the state of New Jersey ended up in wealthy school districts.

Given the demands to produce laborious yet meaningless statistical analyses of themselves and given the use of questionable measures of their teaching effectiveness via student test scores, it is perhaps miraculous that any teachers at all agree to work with inexperienced undergraduates in field placements and in student teaching. However, we might all legitimately ask policy makers what conditions they envision enabling truly deep and risky work with novices in public schools? Are teachers enabled with the time and support to mentor? Are principals and other administrators given the chance to be instructional leaders who foster collaboration and professional growth? Are there incentives and funding necessary to develop actual two-way collaboration between universities and schools?

Induction

The early career phase and its steep learning curve seems more and more like an abandoned concept in today’s policy environment, yet it remains critically important. A simple reality is that regardless of the quality of teacher preparation, there is only just so much that can be done prior to actually teaching. It is not that high quality programs do not prepare teachers more able to take on their full time responsibilities; it is that the mediated and supported environment of teacher education and mentored field experiences cannot fully replicate the reality of full time classroom teaching with the full range of both instructional responsibilities and demands to acculturate to a new school and community. Teachers have been, traditionally, placed into their first classroom on the exact same footing as their experienced peers and expected to perform with only those supports either in place or absent from the schools in which they work.

This is no small matter because, far from the “crisis” of tenured teachers resting on their laurels as portrayed by anti-union activists like Campbell Brown, our schools face a far more serious problem with excessive turn over and the early exit of young teachers from the profession. Richard Ingersoll demonstrates that teacher turnover is a significant phenomenon and a substantial factor in the need for new teachers each year. Additional research by Dr. Ingersoll for the Alliance for Excellent Education calculates that the movement of teachers from one school to another and the replacement of teachers who leave the profession entirely costs upwards of $2.2 billion each year. Dr. Helen Ladd of Duke University reports that in 2008, more than a quarter of our nation’s teachers had five years of experience or less, and that concentrations of teachers with limited experience are found in schools serving underprivileged children. This is especially problematic given that teachers gain in effectiveness very rapidly in the early career with a general leveling off after 15 years of experience; Dr. Ladd’s research found that teachers with that level of experience are generally twice as effective as teachers with only two years in the classroom. Experienced teachers provide schools and students with other advantages as well, but the general point should be clear: we can increase requirements on teacher preparation and upon graduates of teacher preparation all we want, but if the systemic ignoring of the early teaching career continues, those changes will yield nothing.

Researchers from Harvard’s Project on the Next Generation of Teachers have found that working conditions are the strongest predictor of why teachers leave a given school or the profession. Among the school climate elements that impact teacher turnover are the level of trust and support apparent in administration, higher levels of order denoted by matters like student absenteeism and respect, and collegiality in the form of strong support and rapport among teachers. Further, the researchers note that while policy makers can try to impact these aspects of the school environment, they are unlikely to succeed without careful attention to capacity building in the schools and in the district and state offices that seek positive change. For example, expanded and positive collegial interaction requires serious consideration of teaching schedules and administrative duties, so that they can focus upon planning and collaboration with colleagues and curriculum experts, practices that are implemented in higher performing countries. This is not work that can be accomplished on the cheap by rewriting regulations; it needs funding and direct support.

While such initiatives would benefit teachers across the experience levels, special attention should be paid to teachers in the early stage of their career. Before test based accountability dominated the school landscape, we had good evidence that school culture and climate mattered significantly for the success and retention of new teachers. According to Susan M. Kardos and associates, schools that were characterized as having “integrated” professional cultures had a blend of experience levels among teachers and new teachers found high levels of support and sustain collaboration across experience levels that was supported by administrators. In such schools, new teachers were not expected to be polished veterans and found serious efforts taken to provide them with appropriate mentors and to regard them as learning and developing colleagues. Making such environments work requires shared norms that are supported by administrators who work to provide the time and space necessary for productive collaboration across different experience levels of teachers with an expressed goal of improving teaching and learning.

While inspired leadership can build such environments, policy makers can assist by taking the induction period seriously and by seeing that mentoring of new teachers is not a haphazard add on to teachers’ existing work. Feiman-Nemser makes clear that induction of new teachers will happen whether or not it is designed by policy because regardless of the quality of their preparation, new teachers must undertake the following tasks in their early career: gaining local knowledge of students, curriculum, and school context, designing responsive curriculum and instruction, enacting a beginning repertoire in purposeful ways, creating a classroom learning community, developing a professional identity, and learning in and from practice. While quality teacher preparation can lay the groundwork for all of these tasks, they must be implemented within a specific school and community context for a new teacher to be successful, and that process can either be left to chance or policy can seek to increase the number of fruitful contexts for induction so novices are not left to rely upon luck for their specific needs to be recognized and addressed.

Formalizing induction can take different approaches, and policy makers need to carefully consider how they wish to support the matter. Feiman-Nemser observes that promising induction policies seek mentors for new teachers who are appropriate given the context and people involved and allow reduced teaching loads so that novices and mentors can actually collaborate. Strong induction programs also allow for novice development over a period of time, so policy should not confine mentoring and support to just the first year of teaching. Mentors provide genuine and constructive feedback aimed at improving novice practice, and schools and districts provide regular development specific to the needs of novice teachers. Effective mentoring and induction also embraces the dual role of assistance and assessment of novices, so mentors cannot simply confine themselves to a cheer leading role; their practice has to come with tools and dispositions aimed at improving novice teaching. Just as we recognize that the very best students are not always destined to become the very best teachers, we recognize that the very best teachers are not always well-suited for mentoring. Novices need “caring and competent mentors” who are well prepared for their role and given training to understand how to teach teachers. Under ideal circumstances, the mentoring process is two way as mentor teachers, in the process of supporting and teaching novices, sharpen their abilities to observe, analyze, collaborate, assess, coach and other skills important to their improvement of teachers and schools.

It must be noted again that such work and policy does not come without cost. Schools and districts coping with decreased state spending on education, are unlikely to afford resource and personnel intensive policies on their own. If districts can find additional funding, it seems likely they will use it to make up for cuts to programs previously supported by the state (In New Jersey, for example, over 11,000 vulnerable students lost access to after school programs between the hours of 3 and 6pm in the 2011 budget cuts). However, if policy makers are serious about the need for high quality teachers, and if they see the threats to teacher quality and student learning inherent in early career turnover, then they must consider legitimate efforts to create early career induction and mentoring within integrated professional cultures as the norm rather than as lucky exceptions.

###

Policy makers have to consider the kinds of school environments their efforts have developed. Just as teacher stress and job dissatisfaction are serious impediments to recruiting prospective teachers to the field, and just as evaluation requirements that force teachers to create meaningless reports of their teaching and to increase the amount of time spent on test preparation stand in the way of experienced teachers opening their classrooms to novices, those same policies are inherent barriers to instituting deliberate policies of mentoring and induction. Test based accountability and evaluation tasks with little inherent legitimacy but high time commitments are distorting elements in today’s schools. They absorb time and priority from even the very best teachers in our schools, and they given nothing of value in return. Worse, they serve as a disincentive for teachers who would be genuinely accomplished mentors of preservice and early career teachers to even consider taking on the role.

Policy needs a serious realignment to consider what practices can be instituted that would shift accountability from a test and punish focus and into a support and growth focus when it comes to teacher quality. Recruitment of students into teacher preparation can only happen in an environment when the actual rewards of teaching are evident. Most teachers would be unlikely to turn down an offer of better salaries across the board, but by overwhelming margins, teachers want to be able to work for the best of their students and they want more time and resources to do that well. Current policies in most jurisdictions simply pile more work on teachers with fewer resources and demand growth in test scores as the main indicator of success.

Higher demands on teacher education are not made in a vacuum. It may be defensible to seek higher entrance requirements into teacher education and to call for more work in the field by teacher candidates, but the development of genuinely quality partnerships between schools and universities is resource and time intensive work that is difficult to accomplish simply by fiat from state capitols. Capacity must be built at all levels of the system, and resources in the form of money and development time have to be built into the changes for work to be genuinely meaningful. Further, experienced teachers, even those disposed to mentoring, cannot be fairly expected to participate in increased responsibilities for teacher education under current circumstances.

In the era of test based accountability, little attention has been given to the needs of novice teachers during their induction period, and that has continued the long standing and increasingly unsustainable churn in early career teaching. Our schools lose both money and valuable experience as the unique needs in induction remain met only by haphazard circumstance rather than by a systemic focus on novices as learners, colleagues as mentors, and teachers as growing throughout their careers. While school climate cannot be commanded from afar, policy makers ignore the circumstances that they incentivize at the peril of both teachers and students. Induction of novice teachers will happen whether we attend to it or not, and failing to do so in any systemic way perpetuates the current “system” that has no focus or operating principles.

Becoming a teacher is frequently a lengthy journey. Our future teachers are in our public schools right now forming their earliest, and sometimes most enduring, ideals about what purposes are served by public education and what the work of teaching and learning entails. This time period is absolutely essential to the formation of their sense of vocation and commitment to the best ideals of education. Entry into teacher preparation, in many senses, begins with the first desire to be like a child’s favorite teacher, but the path laid before that prospective teacher is one within the influence of policy. If we want that path to be both effective and purposeful, then we need to understand it and use policy to enable its best possibilities.

References:

Alexander, F. (2014, April 21). What Teachers Really Want. The WashingtoN Post. Retrieved April 19, 2015, from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/wp/2014/04/21/what-teachers-really-want/

Alliance for Excellent Education (2014). On the path to equity: Improving the effectiveness of beginning teachers. Washington, DC: Mariana Haynes.

Baker, B. (2014, January 30). An Update on New Jersey’s SGPs: Year 2 – Still not valid! Retrieved April 19, 2015, from https://schoolfinance101.wordpress.com/2014/01/31/an-update-on-new-jerseys-sgps-year-2-still-not-valid/

Berliner, D. (2000). A Personal Response to Those Who Bash Teacher Education. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(5), 358-371.

Cawelti, G. (2006). The Side Effects of NCLB. Educational Leadership, 64(3), 64-68.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). How Teacher Education Matters. Journal of Teacher Education, 51(3), 166-173.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2013, June 18). Why The NCTQ Teacher Prep Rating Are Nonsense. The Washington Post. Retrieved April 19, 2015, from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/wp/2013/06/18/why-the-nctq-teacher-prep-ratings-are-nonsense/

Day, T. (2005). Teachers’ Craft Knowledge: A Constant in Times of Change? Irish Educational Studies, 24(1), 21-30.

Feiman-Nemser, S. (2001). From Preparation to Practice: Designing a Continuum to Strengthen and Sustain Teaching. Teachers College Record, 103(6), 1013-1055.

Fenstermacher, G.D. (1999). Teaching on both sides of the classroom door. In K.A. Sirotnik & R. Soder (Eds.), The beat of a different drummer: Essays on educational renewal in honor of John Goodlad (pp. 186-196). New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

Greene, M. (1978). Teaching: The Question of Personal Reality. Teachers College Record, 80(1), 22-35. Retrieved April 19, 2015, from http://www.tcrecord.org/Content.asp?ContentId=1080

Hadley Dunn, A. (2014, August 3). Fact-Checking Campbell Brown: What she said, what research really shows. The Washington Post. Retrieved April 19, 2015, from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/wp/2014/08/03/fact-checking-campbell-brown-what-she-said-what-research-really-shows/

Hansen, D. (1994). Teaching and the Sense of Vocation. Educational Theory, 44(3), 259-275.

Hargreaves, A. (2009). Presentism, Conservatism, and Individualism: The Legacy of Dan Lortie’s “Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study” Curriculum Inquiry, 40(1), 143-155.

Ingersoll, R. (2001). Teacher Turnover and Teacher Shortages: An Organizational Analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 38(3), 499-534.

Johnson, N., Oliff, P., & Williams, E. (2011, February 9). Update on State Budget Cuts. Retrieved April 19, 2015, from http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=1214

Kardos, S., Moore Johnson, S., Peske, H., Kauffman, D., & Liu, E. (2001). Counting of Colleagues: New Teachers Encounter the Professional Cultures of Their Schools. Educational Administration Quarterly, 37(2), 250-290.

Katz, D. (2015, March 27). Does Anyone in Education Reform Care If Teaching is a Profession? Retrieved April 19, 2015, from https://danielskatz.net/2015/03/27/does-anyone-in-education-reform-care-if-teaching-is-a-profession/.

Ladd, H. (2013, November 24). How Do We Stop the Revolving Door of New Teachers? Atlanta Journal Constitution. Retrieved April 19, 2015, from http://www.ajc.com/weblogs/get-schooled/2013/nov/24/how-do-we-stop-revolving-door-new-teachers/

Leachman, M., & Mai, C. (2014, May 20). Most State Funding Schools Less Than Before the Recession. Retrieved April 19, 2015, from http://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=4011

Lortie, D. (2002). Schoolteacher: A sociological study. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McGuire, K. (2015, February 23). As veteran teachers face more time demands, placing student teachers becomes more difficult. Star Tribune. Retrieved April 19, 2015, from http://www.startribune.com/local/west/293771361.html

MetLife, Inc. (2013). The Metlife Survey of the American Teacher: Challenges for School Leadership. New York, NY: Harris Interaction. Retrieved April 19, 2015, from https://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/foundation/MetLife-Teacher-Survey-2012.pdf.

Moore Johnson, S., Kraft, M., & Papay, J. (2012). How Context Matters in High Needs Schools: The Effects of Teachers’ Working Conditions on Their Professional Satisfaction and Their Students’ Achievement. Teachers College Record, 114(10), 1-39. Retrieved April 19, 2015, from http://www.tcrecord.org/content.asp?contentid=16685.

Ravitch, D. (2014, March 24). How New Jersey is Trying to Break its Teachers. Retrieved April 19, 2015, from http://dianeravitch.net/2014/03/28/teacher-how-new-jersey-is-trying-to-break-its-teachers/

Sahlberg, P. (2015, March 31). Q: What Makes Finnish Teachers So Special? A: It’s Not Brains. The Guardian. Retrieved April 19, 2015, from http://www.theguardian.com/education/2015/mar/31/finnish-teachers-special-train-teach

Sawchuck, S. (2014, October 21). Steep Drops Seen in Teacher-Prep Enrollment Numbers. Edweek. Retrieved April 19, 2015 from http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2014/10/22/09enroll.h34.html.

Simon, N., Moore Johnson, S. (2013). Teacher Turnover in High Poverty Schools: What We Know and Can Do. (Working Paper: Project on the Next Generation of Teachers). Retrieved April 19, 2015, from http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic1231814.files//Teacher%20Turnover%20in%20High-Poverty%20Schools.pdf.

Taylor, A. (2011, December 14). 26 Amazing Facts About Finland’s Unorthodox Education System. Retrieved April 19, 2015, from http://www.businessinsider.com/finland-education-school-2011-12#teachers-are-selected-from-the-top-10-of-graduates-19

Zeichner, K. (2010). Rethinking the Connections Between Campus Courses and Field Experiences in College- And University-Based Teacher Education. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1-2), 89-99.