New York Governor Andrew Cuomo recently sent some mixed signals on his education platform. In late September, he declared that the teacher evaluation system in the Empire State needs “refinement” because even using standardized test scores to create value-added measures, too many teachers are found to be effective or highly effective. This month, however, the Cuomo campaign, perhaps responding to criticisms of his embrace of the Common Core State Standards, issued an ad that suggested a softer approach to education. Featuring Governor Cuomo in a white sweater helping his similarly attired daughter with her homework at a table decorated with white pumpkins and a glass bowl of smooth pebbles, the ad promised “real teacher evaluations” and not using Common Core test scores for “five years.” That promise, however, simply reflects an existing item in the state budget that delays including test scores in graduating students’ transcripts; it does not promise to not use the test scores to evaluate teachers in any way. The governor’s softer, rather beige, image is an illusion.

There was no illusion this week, however.

Speaking with the New York Daily News editorial board, Mr. Cuomo emphasized his priorities on education for a second term in Albany:

“I believe these kinds of changes are probably the single best thing that I can do as governor that’s going to matter long-term,” he said, “to break what is in essence one of the only remaining public monopolies — and that’s what this is, it’s a public monopoly.”

He said the key is to put “real performance measures with some competition, which is why I like charter schools.”

Cuomo said he will push a plan that includes more incentives — and sanctions — that “make it a more rigorous evaluation system.”

The governor took a direct, insulting, swipe at the 600,000 members of the NYSUT, by saying, “The teachers don’t want to do the evaluations and they don’t want to do rigorous evaluations — I get it. I feel exactly opposite.”

It is rare to have one person summarize, so succinctly, nearly everything that is wrong with the current education reform environment. “Break…a public monopoly…competition, which I why I like charter schools…the teachers don’t want to do the evaluations.” In those short turns of phrase, Andrew Cuomo demonstrates how he utterly fails to understand teachers, the corrupted “competition” environment he promotes, and the entire purpose of having a compulsory, common school system. I personally cannot think of any statements he could have made that disqualify him more from having any power over how we educate our young people.

The governor, who expects to win Tuesday’s election by a wide margin, faced immediately backlash over his comments, but he has opted to double down and repeat the rhetoric of calling our state’s public schools a monopoly. He has even gotten harsh criticism from the Working Families Party, whose endorsement he wrestled for this summer when the progressive party looked to ready to endorse Fordham Law School Professor Zephyr Teachout. W.F.P.’s state director, Bill Lipton commented:

“His proposed policies on public education will weaken, not strengthen our public education system, and they would represent a step away from the principle of high quality public education for all students. High stakes testing and competition are not the answer. Investment in the future is the answer, and that means progressive taxation and adequate resources for our schools.”

In return, Governor Cuomo’s campaign spokesman, Peter Kauffmann said, “This is all political blather.” If anyone in the leadership of W.F.P. still has faith in Mr. Cuomo’s promises to them, I will be astonished.

I am going to address Mr. Cuomo’s statements in reverse order:

1) “The teachers don’t want to do the evaluations and they don’t want to do rigorous evaluations”

Mr. Cuomo bases this upon teacher opposition to the “rigorous” evaluations that include the use of students’ standardized test scores to determine if teachers are highly effective, effective, or not effective. Not meeting the “effective” range on the evaluations can cost teachers tenure or it can initiate efforts to remove them from the classroom if they already have tenure. Governor Cuomo is on record as believing that the current system is too lenient on teachers because under the new Common Core aligned examinations, student proficiency in the state has dropped dramatically while, in his view, too many teachers remain rated as effective and highly effective. Presumably, the Governor wants to change the evaluation system so that administrator input is less important and so that the “rigorous” method of rating teachers by students’ test scores has more of an impact on their effectiveness ratings. This is a fatally flawed approach, and it is fated to unleash appalling results for several important reasons.

First, as I have written previously, he has egregiously, and probably deliberately, misrepresented what the student proficiency ratings from the Common Core exams mean. While students reaching proficient and highly proficient on the exams only reached 36% of test takers last year, the cut scores were deliberately set to reflect the percentage of students in the state whose combined SAT scores reflect reasonable first year college performance. Unsurprisingly, the numbers of students who scored at proficient and above almost exactly mirrored the percentage of students with those SAT scores. This cannot be construed as students and their teachers under-performing expectations, and, not for nothing, the percentage of New Yorkers over the age of 25 with a bachelor’s degree is 32.8%.

So let’s be perfectly clear: the Governor is saying that teachers in communities where large percentages of students do not attend college are automatically “not effective” teachers.

Second, the entire CONCEPT of tying teacher performance to standardized test scores rests on controversial premises and is not widely accepted by the research community. The American Statistical Association warns that teacher input can only account for between 1-14% of student variability on standardized test performance, and they also do not believe that any current examination is able to effectively evaluate teacher input on student learning. Further, advocates of value added models tend to make “heroic assumptions” in order to claim causation in their models, and they tend to ignore the complications for their models that arise when you recognize that students in schools are not assigned to teachers randomly.

I know many teachers who wish to improve their teaching and who would welcome a process that gives them good data on how to go about doing that. I know no teachers who want to be subjected to evaluations that rely on flawed assumptions of what can be learned via standardized exams.

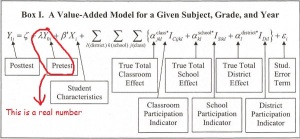

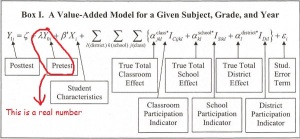

Finally, value added models tend to be incredibly opaque to the people who are evaluated by them. For example, this is the Value Added Model that New York City used in the 2010-2011 school year:

This is also the VAM that found teacher Stacey Issacson to be only in the SEVENTH percentile of teachers despite the fact that in her first year of teaching 65 of 66 students in her class scored “proficient” or above on the state examinations, and more than two dozen of her students in her first years of teaching went on to attend New York City’s selective high schools. Perhaps worse than having a formula spit back such a negative rating was the inability of anyone to actually explain to her what landed her in such a position, and Ms. Issacson, with two Ivy League degrees to her name and the unconditional praise of her principal, could not understand how the model found her so deficient either. Perhaps I can help. In this image I have circled the real number that actually exists prior to value added modeling:

And in this image, I circle everything else:

Consider everything that might impact a student’s test performance that has nothing to do with the teacher. Perhaps he finally got an IEP and is receiving paraprofessional support that improves his scores. Perhaps there is a family situation that distracts him from school work for a period of time during the year. Perhaps he is simply having a burst of cognitive growth because children do not grow in straight lines and is ready for this material at this time, or, subsequently, perhaps he had a developmental burst two years ago and is experiencing a perfectly normal regression to the norm. Value added model advocates pretend that they can account for all of that statistical noise in single student for a single school year, and then they want to fire teachers on those assumptions. This is what happens when macroeconomists get bored and try to use their methods on individual students’ test scores.

Governor Cuomo assumes that because teachers do not want to be subjected to statistically invalid, career ending, evaluations that they do not want to be evaluated.

2) “competition, which I why I like charter schools”

Charter schools were never supposed to be “competition” for the public school system. As originally conceived, they would be schools given temporary charters and be relieved of certain regulations so that they could experiment with ways to teach populations of students who were historically difficult to teach in more traditionally organized schools. In this vision, originally advocated by AFT President Albert Shanker, charter schools would feed the lessons they learned back to the traditional school system in a mutually beneficial way. Governor Cuomo’s idea is as far from that vision as it is possible to be and still be using the same language.

The Governor apparently thinks that charter schools are there to put pressure on fully public schools, and that the “competition” for students will act like a free marketplace to force improvement on the system. This is a gospel that has deep roots, going as far back as Milton Friedman in 1955, and gaining intellectual heft for the voucher movement in the 1990s with Chubb and Moe’s 1990 volume, “Politics, Markets and America’s Schools.” While vouchers have rarely been a popular idea, advocates for competition in public education have transformed charter schools into a parallel system that competes with fully public schools. This has flaws on several levels. First, it is an odd kind of marketplace when one provider is relieved of labor rules and various state and federal education regulations and the other is still held fully accountable for them. Charter schools’ freedom from regulations was meant to allow for innovations that would help traditional schools learn, but instead it has become a “competition” where one competitor is participating in a sack race and the other in a 100 yard dash. A sack race, by the way, is an entirely fine thing to participate in, but no race is legitimate when everyone isn’t required to follow the same rules.

Second, the presence of the charter sector as currently operated and regulated actively makes district schools worse off. As Dr. Baker of Rutgers demonstrates, charter schools generally compete for demographic advantages over fully public schools. They draw from a pool of applicants who are both attuned to the process and willing and/or able to participate in it. Once students are admitted, many prominent charters, especially ones that get high praise from Governor Cuomo, engage in “substantial cream skimming” that results in their student populations being less poor, having fewer students on IEPs, and needing less instruction in English as a Second Language. While charter operators deny engaging in these practices, well documented cases are available in the media. Dr. Baker’s research confirms that when charter schools are able to do this, the district schools in the same community are left with student populations that more heavily concentrate the very populations of children that the charter schools are unwilling to accommodate. Charter advocates then claim that they are getting “better” results with the “same” kids and protest loudly that they deserve a greater share of the finite resources available for schools, even when the costs of their transportation and building expenses are paid by the districts.

This isn’t just a sack racer versus a sprinter, then — the sprinter has slipped a couple of cinder blocks into his opponents’ sacks. Teachers don’t mind that other schools may do things differently than they do in their own schools; they mind very much being berated for the results of system-wide neglect of their community schools, and they mind being negatively compared to schools that make their own rules and refuse to serve all children.

3) “Break…a public monopoly”

That we are poised to have a two term governor who describes New York’s public education system as “monopoly” is such a breath taking circumstance, that I am saddened beyond belief. The common schools movement in this country was conceived of as an exercise in promoting the public good not merely in advancing individuals. We wanted universal, compulsory, free education to serve the individual by promoting academic and economic merit as well by promoting the habits of mind and character that enrich a person’s experience in life. We also wanted schools to promote the good of society by preparing individuals for the world of work beyond school and by preparing individuals to be thoughtful participants in our democracy who value civic virtues in addition to their own good. For nearly two centuries, Americans have thought of public schools as the center of community civic life, something to be valued because it provides bedrock principles of democratic equality, and as our concept of democratic participation has expanded, so has our concept of plurality in schools. From literacy for former slaves to women’s suffrage to incorporation of immigrants to tearing down White Supremacism and promoting civil rights, to inclusion of those with disabilities, to gender equality, to equal protection for LGBT citizens — our schools have helped us to reconceive our ideas of pluralism in every decade.

Schools have also stood as important symbols of our commitment to common aspects of our society that all have access to regardless of race, gender, or economic advantage. There was a time in our nation’s history when we were dedicated not merely to building economic infrastructure, but also to building community, cultural, and natural infrastructure. There are libraries, parks, museums, and publicly supported arts across our country that are testament to the belief that the world of knowledge, natural beauty, and the arts cannot be the sole province of the wealthy. Public schools are part of that commitment, but to call them a “monopoly” reveals a mindset disregarding that heritage and which rejects it as a commitment to the future. Does Governor Cuomo drive the New York Throughway and see a “public monopoly”? Does he enter the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City whose entry fee is a suggested donation and see a “public monopoly”? Does he want to “break up” the Franklin D. Roosevelt and Watkins Glen State Parks?

What Governor Cuomo appears to believe is that education exists solely for the social mobility of individuals with no regard for the public purposes of education. David Labaree of Stanford University posited in this 1997 essay, that the historic balance of purposes in education was already out of balance with current trends favoring education for individual social mobility far outweighing the public purposes of social efficiency and democratic equality. Labaree was rightly concerned that if people only see education as the accumulation of credentials that can be turned in for economic advantage then not only will the civic purposes of education be swept aside, but also that the effort to accumulate the most valuable credentials for the least effort will diminish actual learning. Governor Cuomo’s depiction of schools as a “public monopoly” only makes sense if he is mostly concerned with how education “consumers” accumulate valued goods from school, but discounts the essential services schools provide to our democracy. It is an impoverished view that relegates school to just another mechanism to sort people in and out of economic advantage.

Governor Andrew Cuomo may not only be at war with teachers. He may be at war with the very concept of public education. If he does indeed win a second term on Tuesday, he must be opposed at every step of his distorted and dangerous ideas about our public schools.