This week, our teacher preparation program welcomes the graduates of the Class of 2015 as our teacher colleagues. These accomplished young teachers are joining the profession at a time of great challenges, but it is also at a time of great opportunities, and having worked with them closely for the past four years, I am convinced that they will do well with those opportunities. These young people are intelligent; they are dedicated; they are talented; and they are prepared. It has been an immense pleasure to see their professional journeys.

It would be a disservice to them to downplay the challenges they face as new members of the profession. Today’s graduates were mostly born in 1993 which means that they were in third grade when the No Child Left Behind Act in 2001 mandated annual standardized testing for all children in all grades between three and eight and once again in high school. They went through their formative elementary and secondary education as the high stakes attached to mandated testing was squeezing the curriculum into a narrower box with less art, music, social studies, and science. While the impacts of Race to the Top, the Common Core State Standards, and PARCC and SBAC testing did not influence their education, they have done their clinical internships and student teaching within schools and with cooperating teachers who have had to grapple with these issues as well as the growing movement of parents who are denying schools the right to administer standardized tests to their children.

Now they leave their university preparation to enter teaching just as these matters are fully breaking upon our schools. The CCSS are implemented in 43 states and the District of Columbia. Mass standardized examinations aligned with the standards are now implemented in dozens of states, and they promise to find many fewer students proficient in mathematics and English than just a year ago. States that won Race to the Top grants or were granted NCLB waivers from the USDOE are using growth measures based on standardized testing to evaluate teachers, despite the fact that the sum of research on growth measures demonstrates that they are unstable, unreliable, and have standard errors so large that even with 10 years of data, a teacher still has more than a 10% chance of being mislabeled.

If these challenges were not hard enough, the confluence of hastily implemented and ill-conceived policies comes amidst a rhetorical turn against teachers as the major culprits behind students whose test scores do not rise. Today’s reform environment lavishes transformational power upon education, but it simultaneously measures that transformation via crudely designed standardized tests and then blames allegedly incompetent teachers when literally nothing else is done to improve the lives or communities of students who struggle. A coordinated effort is underway to first assess teachers via standardized test results and then to remove any workplace protections teacher have to make it easier to fire them at will. It is little wonder that the percentage of teachers who say they are highly satisfied on the job has dropped 30 percentage points to its lowest in a generation.

A distressing side effect of this environment are the number of more experienced teachers who appear ready to discourage our new colleagues from either entering the field altogether or from bothering to have hope on the job. Peter Greene of Curmudgucation reminds us that this is a distressing and unethical practice, and he points out the specific work of the activists in the Young Teachers Collective who are directly asking their experienced colleagues to stop discouraging them.

I hope to G-d that my proud young graduates side with the activists at YTC. We need them very badly.

Unlike Baby Boomers and my fellow Gen Xers who indulge in annual, graduation week denigration of the Millennials for their supposed faults, I am a fan of this generation. Having worked closely with them for years now, I find this report on their outstanding and community oriented values to be absolutely correct. Young adults today are more diverse than their predecessors, more open to diversity than any generation in history, better educated than anyone gives them credit for, and more desirous of being good parents and good neighbors than of the aggrandizement of self typified by generations who modeled our lives after Gordon Gekko.

So let me build on Peter’s plea for people to not be jerks to young teachers, and to add my own plea: young teachers, we need you. We need you because you have been well-prepared. We need you because if you do not stay we will have wasted the earned experience and skills you will gain in your first decade on the job, and that will harm future students. We also need you because of those same values that typify your generation and which will serve as a tremendous asset to protect and preserve truly public education.

But if that is going to happen, we also need you to buck some typical trends in teaching and schooling. It is very typical for teachers to simply keep their heads low, close the door, and wait for the current political tides to shift. That is unlikely to work today; people are getting rich messing around with our schools, and they see our nation’s commitment to education for all as a $780 billion honeypot to monetize. The good news in the midst of this is that the people still back our public schools, and while many have bought the relentless narrative that our schools writ large are failing, parents overwhelmingly support the schools their children attend. You can generally count on the support of your students’ parents.

We need you, therefore, to be confident in that support and to help lend a voice, early in your careers, for certain truths that can reach the public only if they are amplified by many voices:

We need you to remind people that school and teachers cannot do it all alone. Education is a likely component of most success stories in our country, but education did not play its role in those successes alone. Education reform talks about education as key to overcoming poverty, but it spends very little time talking about how the advantage gap is overcome by much more than “grit” and “no excuses.” We certainly see few reformers admit the severe funding gaps between our richest and poorest schools, and Governor Andrew Cuomo of New York has openly scoffed that funding has any role to play in educational inequities.

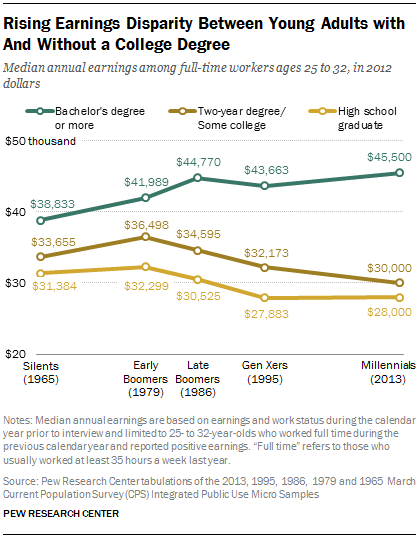

But even beyond that issue, there is a question about the central premise of education reform today; namely, if all students acquired more and better education, would they be able to leap over poverty in their careers? The evidence for this is unclear because even though college degree holders greatly out earn non degree holders, that gap has grown because of cratering wages for less education rather than growing wages for more:

Increasing numbers of college degree holders will not magically create more middle class households unless the number of jobs genuinely requiring college education increase as well. Education reformers who tout the power of standards and testing to prepare students who are “college and career ready” would do well to ask their billionaire backers to support middle class economics and actually be “job creators” if they really believe education will overcome poverty. It won’t without fundamental changes in economic opportunity on the other side of education.

We need young teachers to speak up for fundamental truths about their children in communities of poverty. Grit and no excuses make for great bumper stickers and they can produce test practice mills that result in test scores. But truly standing up for children is more than sloganeering and shutting down schools whose children are hungry and live in communities with few genuine opportunities. The reality is that in many of our urban communities, black and brown children go to schools with inexperienced teachers, limited services, crumbling facilities, and over crowded classrooms and then go home to neighborhoods that have been in economic decline for decades. None of the favored reforms today are doing anything to alleviate those conditions, and many of them are making them actively worse.

We need young teachers in such communities to have the bravery of Marylin Zuniga who has lost her job teaching third graders for a series of events based on her desire to embrace both action and compassion. Ms. Zuniga had her students read and discuss a quote about justice from Mumia Abu-Jamal who was convicted of murdering a police officer in a 1981 trial that drew strong questions about the fairness of the trial and of the appeals court from Amnesty International. Later in the year, Ms. Zuniga allowed her students to write get well letters to Mr. Abu-Jamal when she told them he was sick and they wanted to write to him. While Mr. Abu-Jamal’s case stirs very strong emotion, especially among law enforcement, it is important to consider what Ms. Zuniga was doing with her students, most of whom are children of color in a poor neighborhood: she asked them to consider the legitimate voice of a black man in prison whose case raises difficult questions about the justice system, and on their own, the children showed and exercised compassion. For young people whose lives are already disrupted by family members in trouble with the criminal justice system, this is a lesson with risks that are worth exploring. And many in her community rushed to support her even though they were unsuccessful.

If we truly care about the children in poverty in our schools, we need more teachers willing to take such risks and to affirm their students’ desires to see humanity in everyone. We need them to assert and to affirm their values of inclusiveness and human dignity even if it means taking a risk. Many decried Ms. Zuniga’s actions, but those who knew her the best affirmed the extraordinary stewardship she exercised for children who are already struggling.

We need young teachers to stand together. There are many forces trying to fragment teachers from working together for their students’ true interests. There are AstroTurf groups like “Educators 4 Excellence” who take large sums of money to act like a genuine grassroots group but whose pledge includes supporting discredited teacher evaluation methods favored by union busting corporate donors. There is the “Education Post” headed by Peter Cunningham, formerly of the Obama Administration, and funded with millions of dollars from Eli Broad and the Walton Family Foundation to make a “better conversation” but mostly to pay people to respond to criticisms of education reform as if they have grassroots support.

So when I plead with young teachers to “stand together” I do not just mean to join your union and be active (although, yes, I do mean that too). I also mean to do what your generation does better than any of us — maintain close and genuine bonds across distance via technology and to forge naturally occurring and completely authentic communities to support each other and to support your students. Talk to each other. Share ideas. Plan. Respond in the public sphere. Magnify your voices. Make stories of public school success go viral. You have something that corporate reformers can never replicate: you have authenticity. Use it.

So, Class of 2015, welcome to our profession. I am honored that you are my colleagues. Please stay. Please lead.