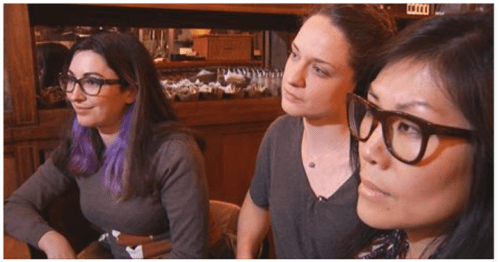

New York City teachers Jia Lee, Lauren Cohen, and Kristin Taylor risked disciplinary action recently to speak with NBC news about their opposition to the state testing system and their support of the Opt Out movement.

This was no small act on their part because the NYC DOE has sent multiple signals that it does not tolerate classroom teachers speaking against the tests which have been occupying schools’ time and attention this month. District 15 Superintendent Anita Skop stated her belief that any teacher encouraging opt outs was engaging in political speech and that such acts were not permissible for teachers speaking as teachers. A spokeswoman for the Department of Education said that teachers are free to speak as private citizens but not to speak as “representatives of the department,” and New York City Schools Chancellor Carmen Farina said “I don’t think that the teachers’ putting themselves in the middle of it is a good idea.” None of these figures have specified what possible consequences could befall teachers for speaking in favor of opt out and against the state standardized tests – but the ambiguous statements alone are sufficient to deter many city teachers from speaking their mind. Add in the history of “gag orders” that prevent teachers from discussing the contents of the examinations – even as professionals seeking to improve tests after they have been used – and speaking to the media as these teachers did is an act of exceptional bravery.

Walking the line between teacher and “private citizen” is exceptionally ambiguous. Ms. Lee, Ms. Cohen, and Ms. Taylor were all identified as New York City teachers by the reporter in the story, but does that automatically make them not private citizens? Most members of our society are not required to hide their professions when speaking on political matters within the public sphere, and in many communities, teachers’ identities are well known to parents, making the distinction between their professional and private selves far less distinct. Furthermore, as professionals in a school system governed by different political systems, teachers have legitimate observations and, yes, criticism to make about policies that impact their work and, therefore, their students. Simply saying teachers cannot be “political” as teachers is plainly too simplistic.

However, this cannot be only a matter of saying teachers have free speech rights in their role as teachers. There are legal and legitimate limitations on what teachers can say. For example, federal law protects the privacy of students’ academic records and while a teacher can discuss a child’s performance with both parents and involved professionals in pursuit of helping that child, the law prevents that same teacher from discussing the child’s academic record outside of that context. Teachers also possess academic freedom within the classroom, but that is not well defined, subject to significant limitations and considerations of the interests of school boards, communities, parents, and children. Generally, teachers have to balance their rights with their significant responsibilities within the classroom, including their responsibility to the adopted curriculum in a district.

Outside of the classroom, teachers also have limits on what they can say and for good reasons. The 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against a teacher who claimed her free speech rights were violated when she was fired for keeping a public blog full of insults about students and parents in her school. This is fundamentally different than writing about politics or using a public forum like letters to the editor to speak about “matters of public concern” as a citizen — her speech gave parents legitimate reasons to demand that she not teach their children. The Washington branch of the ACLU maintains a page with various examples of speech scenarios in which a teacher may or may not be protected from job consequences, and the examples demonstrate that teachers often have additional constraints on their speech related to their ability to perform their responsibilities. On the other hand, purely political speech, even related to education issues, can be strongly protected outside of the classroom.

Consider the case of Boston long term substitute teacher Jeffrey Herman who testified at a Boston City Council meeting against the expense of maintaining a Junior ROTC program in the city and advocating what he believed was a better use of those funds – and who was screamed at by the head of Boston English High School and essentially blacklisted from working there. While that case was settled with no admission of wrongdoing by the city, the implication is clear enough: Mr. Herman was entirely within his rights to speak in the public sphere on a matter of public concern. A staff attorney for the ACLU made this obvious: “Teachers are entitled to political opinions just like everyone else…We need them to feel free to share those opinions with public and elected officials, outside the school, without fear of losing their jobs for doing so. Jeff Herman had a right to speak out at City Hall about Boston spending over a million dollars on JROTC…”

This would seem to neatly point towards a general right for teachers to speak critically of standardized testing and in favor of opt out as long as they do not suggest that they are speaking for district and school administrations in the process. While teachers are obligated to teach the adopted curriculum of the school and to participate in duties such as test administration, critiques of both the curriculum and testing are matters of public concern. Administrators can probably restrict teachers from proactively soliciting opt outs on the school grounds, but they would be beyond bounds to restrict teachers from speaking elsewhere – even if their audience knows that they are teachers. Further, if asked by parents about the tests, it is very plausible that teachers have the right to offer an informed and critical perspective. Grumbling from Tweed Courthouse notwithstanding, Ms. Lee, Ms. Cohen, and Ms Taylor should be secure in their advocacy and their speaking with reporters.

But perhaps this should not merely be a matter of whether or not teachers disciplined for speaking against testing could win a civil rights suit. Perhaps this needs to be framed as a matter of professionalism and professional judgement because while teachers have responsibilities and rights in the performance of their work, they also have professional obligations and norms that define what it means to be a teacher. Among those is the need to speak up when children are being ill served or harmed by what is going on within school. John Goodlad referred to practicing “good moral stewardship of schools” and this principle is as important to teaching as “do no harm” is for medicine or being a zealous advocate is for law. Teachers are given an awesome and sacred trust – the intellectual, social, and emotional well being and growth of other people’s children. Speaking out when that trust is in jeopardy is not simply a question of Constitutional rights. It is a moral obligation.

Do teachers have good reason for concern about how these tests impact their stewardship? New York City teacher Katie Lapham certainly makes a compelling case:

The reading passages were excerpts and articles from authentic texts (magazines and books). Pearson, the NYSED or Questar did a poor job of selecting and contextualizing the excerpts in the student test booklets. How many students actually read the one-to-two sentence summaries that appeared at the beginning of the stories? One excerpt in particular contained numerous characters and settings and no clear story focus. The vocabulary in the non-fiction passages was very technical and specific to topics largely unfamiliar to the average third grader. In other words, the passages were not meaningful. Many students could not connect the text-to-self nor could they tap into prior knowledge to facilitate comprehension.

The questions were confusing. They were so sophisticated that it appeared incongruous to me to watch a third grader wiggle her tooth while simultaneously struggle to answer high school-level questions. How does one paragraph relate to another?, for example. Unfortunately, I can’t disclose more. The multiple-choice answer choices were tricky, too. Students had to figure out the best answer among four answer choices, one of which was perfectly reasonable but not the best answer.

NYSED claims they removed time limits from the test in order to remove performance pressure from very young children, but there are documented cases of this actually matter the exams worse for students. A Brooklyn teacher blogging anonymously notes:

This afternoon I saw one of my former students still working on her ELA test at 2:45 pm. Her face was pained and she looked exhausted. She had worked on her test until dismissal for the first two days of testing as well. 18 hours. She’s 9.

This is a student who is far above grade level in reading, writing and every measurable area imaginable. She definitely got a 3 or 4 on this test. She is a hard worker and powers through challenges with quiet strength and determination. She is not “coddled.” She is sweet, brilliant and creative and as far as I know she has always loved school. She is also shy and a perfectionist.

After 18 hours of testing over 3 days, she emerged from the classroom in a daze. I asked her if she was ok, and offered her a hug. She actually fell into my arms and burst into tears. I tried to cheer her up but my heart was breaking. She asked if she could draw for a while in my room to calm down and then cried over her drawing for the next 20 minutes.

New York City education advocate Leonie Haimson reported on numerous items of test content that she was able to glean from various sources. They included a sixth grade test including a 17th century poem often studied in college, obscure vocabulary in the 8th grade exam, disturbing product placements within reading passages, and missing prep pages without adequate instructions on how to assist students.

Beyond these specific examples, teachers can be rightly concerned about the entire environment within which these exams take place. Since No Child Left Behind was passed in 2001, testing and test preparation have become more and more ends unto themselves instead of quiet background monitoring of the school system. We have spent more than a decade now in a policy cycle based upon “test-label-punish” without considering how to give schools teaching our most vulnerable students the resources and supports needed to do right by those children, their families, and communities. And we have very, very little to show for it except a narrowing curriculum in communities across the country and a crushing increase of academic work at younger and younger ages despite the abject harm it inflicts upon children who need play to learn and to be healthy. Practicing “good stewardship” as a professional teacher clearly embraces openly objecting to these harmful practices.

Ms. Lee told NBC, ““Parents should definitely opt out. Refuse. Boycott these tests because change will not happen with compliance.” She went on to call herself a “conscientious objector.”

She is also a true professional, guarding the well being of the children entrusted to her.